Cartoonists hit at ‘The ASEAN Way’

BANGKOK, THAILAND // SEA-Junction, in collaboration with Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR), produced an engaging and thought-provoking collection of works by artists from across Southeast Asia titled “Cartooning the ASEAN Way of Non-Interference and Consensus” at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC). The exhibition uses the power of cartoons and comics to spark critical conversations about the role of ASEAN in addressing the region’s pressing issues.

By Michi Emma

These works were selected from a recent Cartoons and Comics Competition, where participants creatively explored ASEAN’s long standing principles of “Consensus” and “Non-Interference.” While these principles have historically supported unity and respect for national sovereignty, they are increasingly scrutinised as the region faces ongoing human rights crises and transnational challenges.

These works were selected from a recent Cartoons and Comics Competition, where participants creatively explored ASEAN’s long standing principles of “Consensus” and “Non-Interference.” While these principles have historically supported unity and respect for national sovereignty, they are increasingly scrutinised as the region faces ongoing human rights crises and transnational challenges.

With a focus on transparency, accountability, and inclusivity, the exhibition aims to inspire a vision of ASEAN that goes beyond diplomatic protocol to genuinely uphold human rights and address the needs of its citizens.

The opening ceremony, held on October 22th, featured notable speakers who provided insights into the complex dynamics of ASEAN and its impact on the region’s people.

“ASEAN has failed to address Myanmar’s crisis,“stated Khin Ohmar, a peace and security advocate from Myanmar who is currently advising the organization Progressive Voice. “I have been engaging with ASEAN since 2004. People often assume I am inside the meetings, speaking with officials. But that’s not the case. ASEAN has kept its doors closed to civil society. It’s a powerful elite club where there’s little room for people like us. We’ve worked tirelessly to get ASEAN to prioritise human rights, especially under Myanmar’s brutal military rule”, voicing frustration over its failure to include concrete protections for human rights.

“When Myanmar’s military, under General Than Shwe, sent ‘representatives’ for human rights and children’s rights, we knew these were not truly representative voices. They could not address the issues facing people on the ground,” Ohmar recounted. Her attempts to engage representatives from Indonesia and Thailand were also stymied. “I even travelled to Jakarta to personally deliver documents to the ASEAN Secretariat, but we were turned away.”

ASEAN, she argued, needs to be more than a “caring and sharing community” in name only. “For years, we were told to be patient. But now, with Myanmar’s military using airstrikes on civilians, over 3,400 lives have been lost in the past three and a half years—children, families, people fleeing bombed villages.”

Khin Ohmar praised ASEAN’s 2021 decision not to invite Myanmar’s military chief, Min Aung Hlaing, to official summits, but insisted it was not enough. “ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar is not being upheld. The first point calls for an end to violence, yet the violence has only intensified. For years, we were told to be patient. Yet, despite the Five-Point Consensus to end violence, the military’s brutal airstrikes continue—killing thousands and displacing countless civilians including children. The international community, including the UN, cannot keep hiding behind ASEAN’s inaction. Myanmar’s people have been advancing the struggle for democracy on their own. It’s time for ASEAN to step up, support the people of Myanmar, and truly contribute to peace and stability in the region.”

Founder of the Ministry of Farang Affairs page, long-time Bangkok based French political cartoonist Stéphane Peray spoke about the growing challenges facing his profession. “I have been a political cartoonist for 30 years, and it’s never been easy,” he said. “Media outlets don’t want controversy; they quickly pull cartoons when readers complain, and we end up losing our jobs. I love this work, but it’s become harder to publish, especially in English-language papers. Even The New York Times stopped running political cartoons.“

He pointed out that cartoons are more than simple expressions of opinion; they encapsulate powerful messages that can critique and provoke. “But now, we’re also seeing a trend where more extreme right-wing cartoonists are gaining visibility—something that was unheard of years ago. Political cartooning is changing, not always for the better.”

Peray noted another disturbing trend in the industry, including the struggles of Myanmar cartoonists forced to flee to Thailand. “In Europe, people are shocked to see cartoonists in Myanmar driven out by pressure from authorities. It shouldn’t be like this.”

He also reflected on his own experiences in France after the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks. “That incident changed everything—newspapers became scared to hire cartoonists, fearing the risks. The intimidation worked.” Despite this, Peray expressed optimism for the next generation. “I have been a judge in many competitions, and I am impressed by young artists. They are skilled at delivering clear, powerful messages—something crucial in political cartooning.“

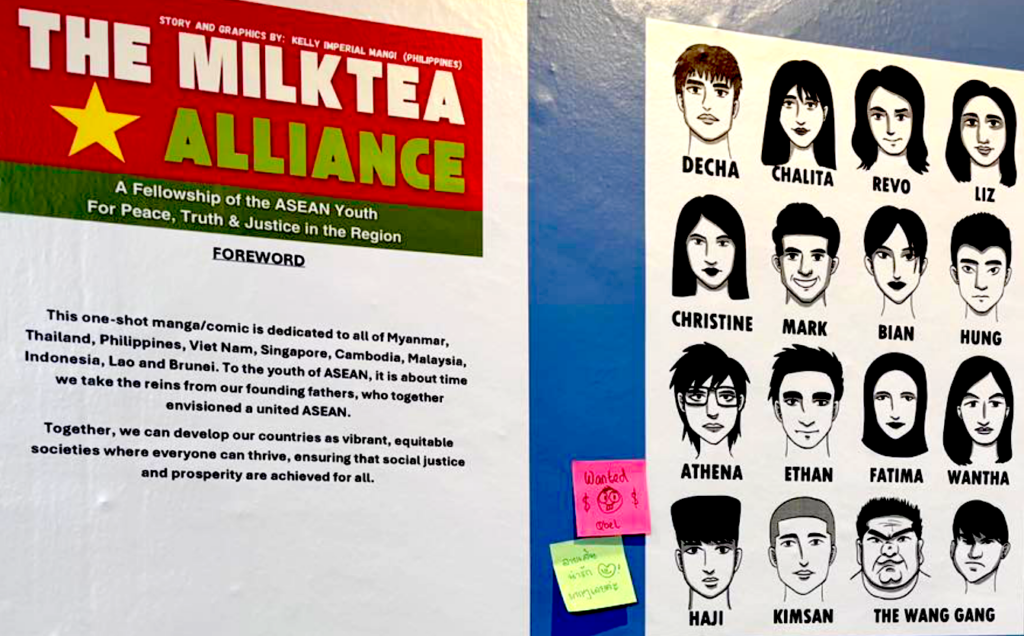

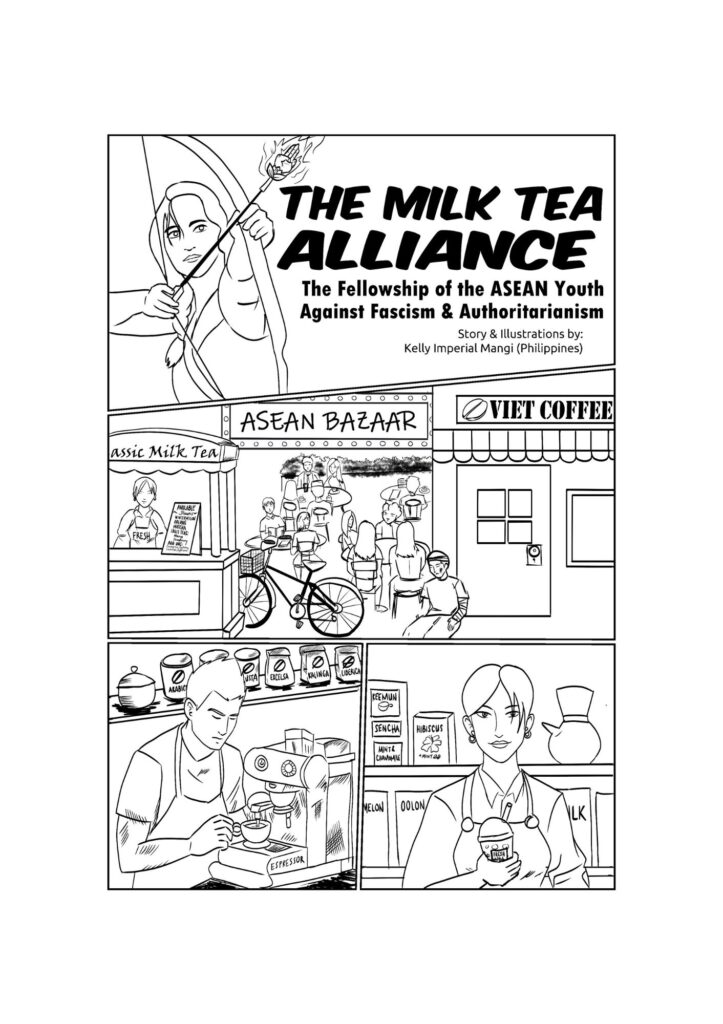

Kelly Twinkle I. Mangi, who received a Special Mention in the Comics Category from the Philippines, spoke on her work as a cartoonist during the Covid-19 pandemic. “During that time, we built connections across regions, discussing humanity, not politics, in my classes at the university. But government restrictions were harsh. Criticise, and you risk jail.”

Inspired by the political climate, Kelly posted her cartoons online, “Filipinos enjoy humour; it helps them connect with deeper issues. Political cartoons are popular here, with clear messages against government actions”.

Kelly also engaged with activist groups to foster regional support. “We started connecting with groups from Thailand and Cambodia, like the ‘Milk Tea Alliance,’ to bring attention to Southeast Asian youth movements for justice.”

Through this display, the exhibition hopes to engage visitors with the theme of regional governance and stimulate conversation on ASEAN’s future. Ultimately, the organizers envision these works inspiring meaningful discussions on building a genuinely “people-centered” ASEAN Community.

Also through the lenses of artists from diverse backgrounds, the exhibition reminds us that art can be both a mirror and a catalyst—reflecting the current state of ASEAN while inspiring steps toward greater unity, understanding, and collective growth.

You can find the full list of winners to the competition on SEA-Junction website.

Among them, four participants in both the cartoons and the comics categories shared their hopes and realities with our team.

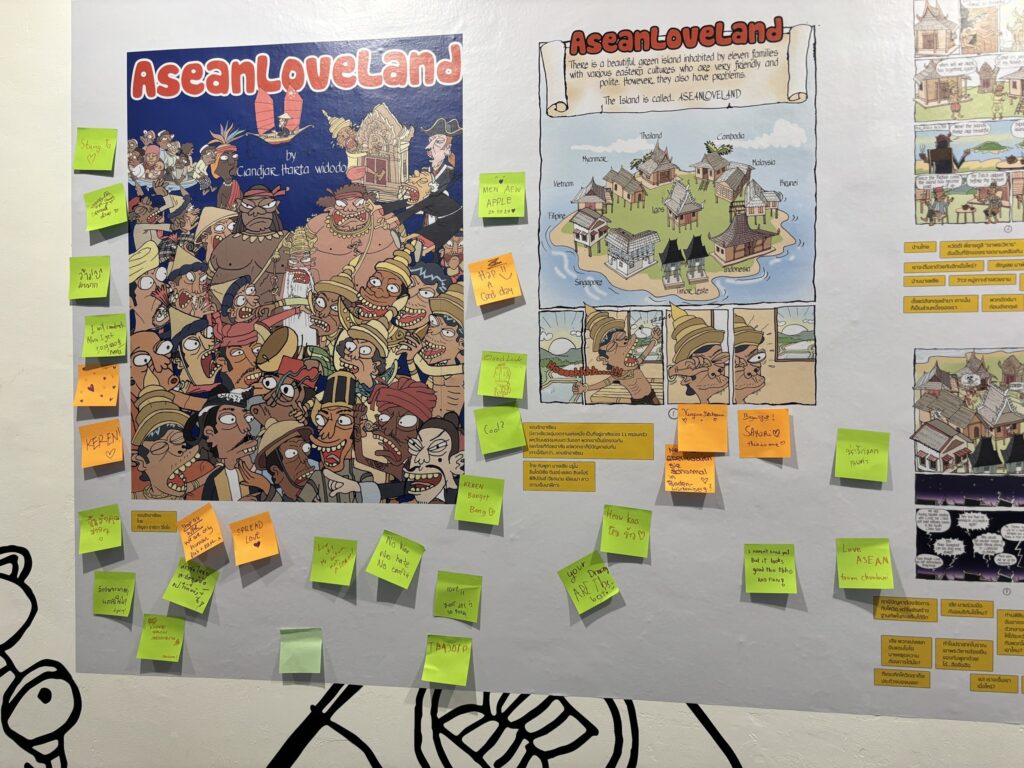

Gandjar Harta Widodo, the 1st Prize Winner in the Comics Category from Indonesia, also shared insights into his journey from a frustrated writer to a celebrated cartoonist. “Becoming a cartoonist was not my plan,” he explained. Initially focused on storytelling, he faced a pivotal moment when his boss told him he could no longer write after a story on a particular company. “I had all these stories and facts I wanted to share, but my boss didn’t see me as a writer anymore. So, with encouragement from a few colleagues, I turned to comics”.

This switch proved transformative. Through cartoons, Gandjar found a new voice, able to address Indonesia’s political climate in a way that words alone could not. “Politics here is complicated. You need to express things carefully to avoid offending people or stirring up anger.” His comics take a unique approach, blending humour with social commentary to address sensitive issues without provoking negative reactions.

One of his well-known creations aka the first prize comic, ASEAN Loveland, tackles problems shared across Southeast Asia, making Gandjar’s work resonate widely across the region. “People across ASEAN have similar cultures, and our leaders all seem to want the same thing—power. Through ‘ASEAN Loveland,’ I try to capture this shared struggle and the fate of the people”.

Kelly Twinkle I. Mangi shared how her comic Milk Tea reflects the growing political awareness among Southeast Asian youth. The comic represents how young people from different ASEAN countries respond to issues like organised crime and authoritarian rule.

Kelly explained, “Each character in my comic reflects how youth in their country perceive regional challenges, such as human rights abuses and corrupt governments.” Drawing inspiration from the Thai response to Myanmar’s crisis, she highlighted the shared struggles of ASEAN nations. “Despite varying political situations, all ASEAN countries suffer from bad governance, and it’s up to our generation to drive change.”

Kelly also discussed the challenges of conveying ASEAN’s principles of non-interference and consensus in her art. “Sovereignty shouldn’t prevent us from addressing regional issues together,” she said. She pointed to the collective action seen in countries like Thailand and Myanmar, emphasising that nations claiming democracy need to communicate and collaborate on common problems.

On the role of artists in political discourse, Kelly noted, “Art communicates ideas quickly, especially in an age of short attention spans. It has the power to challenge tyranny and injustice in a way that everyone can relate to, regardless of their background.” Through her comics, she hopes to inspire Southeast Asian youth to act and push for meaningful change.

Kyaw Lin, a 3D animator and illustrator from Myanmar, was awarded a special mention for his work highlighting the ongoing crisis in Myanmar. Through his platform, art4cdm, he shares the stories of Myanmar’s CDMers and activists, keeping the international community informed.

In his interview, Kyaw Lin discussed his frustrations with ASEAN’s approach to Myanmar. “The principles of non-interference and consensus are impractical. It is impossible for all ASEAN member states to agree on every issue, and this prevents real action. The Myanmar case is a perfect example, where some countries want stronger action against the military junta, while others hesitate, leading to a lack of progress.” The Five-Point Consensus, introduced three years ago, has yet to be implemented.

Kyaw Lin believes that ASEAN should replace consensus with majority rule. “There are countries that genuinely want Myanmar to return to democracy. If decisions were based on majority rule, ASEAN could help end the conflict more quickly”.

His comic Cyber-Scam reflects the consequences of ASEAN’s inaction, particularly the human cost of a dire economic situation pushing people into criminal enterprises. “People continue to suffer in scam centres and under the military junta’s control, while ASEAN remains paralyzed.”

[ Read our series profiling David, a young Burmese man who was sent to work in Dubai scamming centres. ]

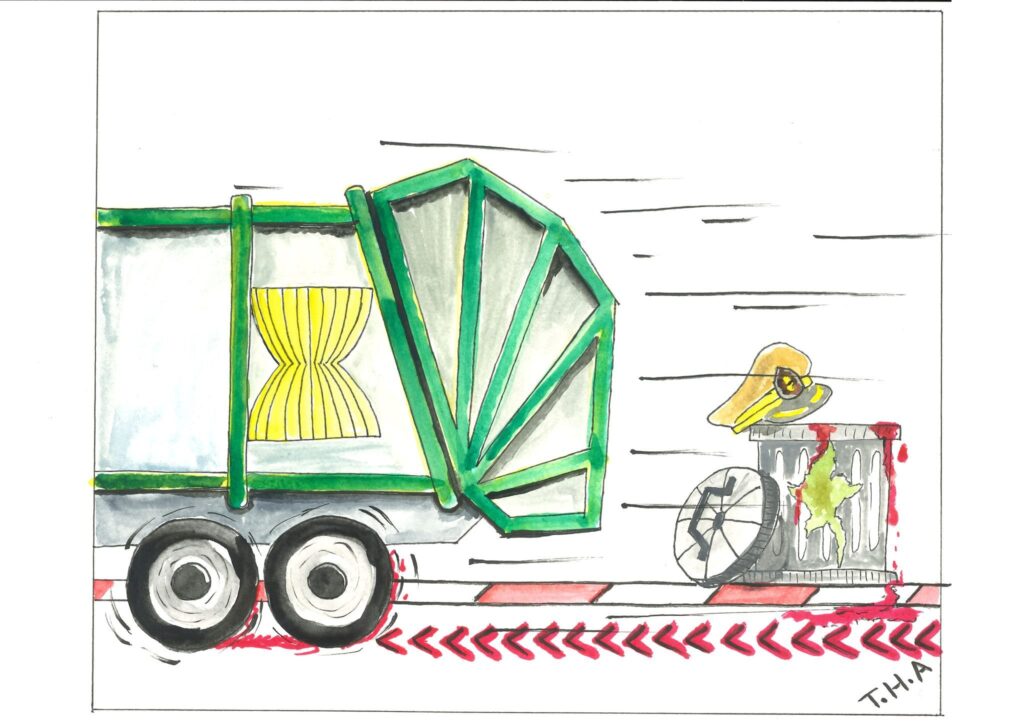

T.H.A, a political cartoonist from Myanmar, shared his challenges and journey in creating impactful art. “My challenge is to make it easy for everyone to understand,” he explained. His work aims to highlight a key message: no authority is good.

T.H.A expressed frustration with the lack of encouragement for critical art. “If there is any support, it’s not from the governments of various Asian countries. Every leader is a dictator in some form.” Through his simple and humorous cartoons, T.H.A strives to convey his powerful critiques towards the authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia.

You can follow his work on Instagram.

T.H.A and Michi Emma, the author of this article, are regular contributors to Visual Rebellion. In partnership with French academic research-center IRASEC, their cartoons were recently published in “Defiance, civil resistance and experiences of violence under military rule in Myanmar” (Chapter 4 from page 95)

/ Our fellowship / The “Cartooning for Myanmar” project, set up by Info Birmanie and Visual Rebellion and supported by the City of Paris, brings together 7 Burmese cartoonists in exile who are determined to bear witness to what is happening in their country and to learn about press cartooning, by offering them the chance to get involved in a project to create an exhibition in France tracing the situation in Myanmar since the military coup of 1 February 2021 through press cartoons.