The Full Moon of Darkness: Massacre in Sipa Village

200 soldiers stormed the village, and in three separate groups, ignited fires from all sides. These are the actions of the same military that has since 1948 illegitimately claimed the inalienable mandate to protect the people of Myanmar, and has sought to crush democracy movements across multiple generations in order to do so.

SIPA, BUDALIN TOWNSHIP, SAGAING REGION // Ma Myint* was selling her homegrown vegetables in a neighbouring village, on October 17th when she heard of the military’s approach.

To avoid confrontation, she chose not to return home to Sipa, in Budalin Township, roughly 130km as the crow flies from Mandalay, the country’s second largest city.

Ma Myint’s mother, in her seventies, and younger brother, suffering from paralysis, were transported to safety by a cousin in a cow-cart, after also hearing the news.

Of her 76-year-old father, U Tin Hlaing, Ma Myint knew only that he had sought refuge in a small hut near the village monastery. It was two days later, on October 19th, when the devastating news finally reached her:

He did not die a natural death; he was brutally killed by soldiers who came to the village on October 17. We heard that he had been killed, his head chopped off by the military.

Unable to bear the thought of seeing her father’s body in that condition, she was robbed of closure, and of being able to farewell her father one last time.

We didn’t have the courage to see him after hearing that his head had been chopped off. How could we have the strength to see it, even though we felt very upset that we couldn’t be there for his final journey.

Sipa, a village of 1000 people with 500 houses, had been home to Ma Myint her entire life.

Yet on the day of the Festival of Light, two military columns entered the village, setting fire to homes and brutalizing the community. The soldiers tortured and killed six men in total—five Sipa villagers and another person they had kidnapped from elsewhere. It is common for the military to use innocents, sometimes children and the elderly, to walk ahead of them in their operations as porters, to be the first to detonate any landmines that may be ahead.

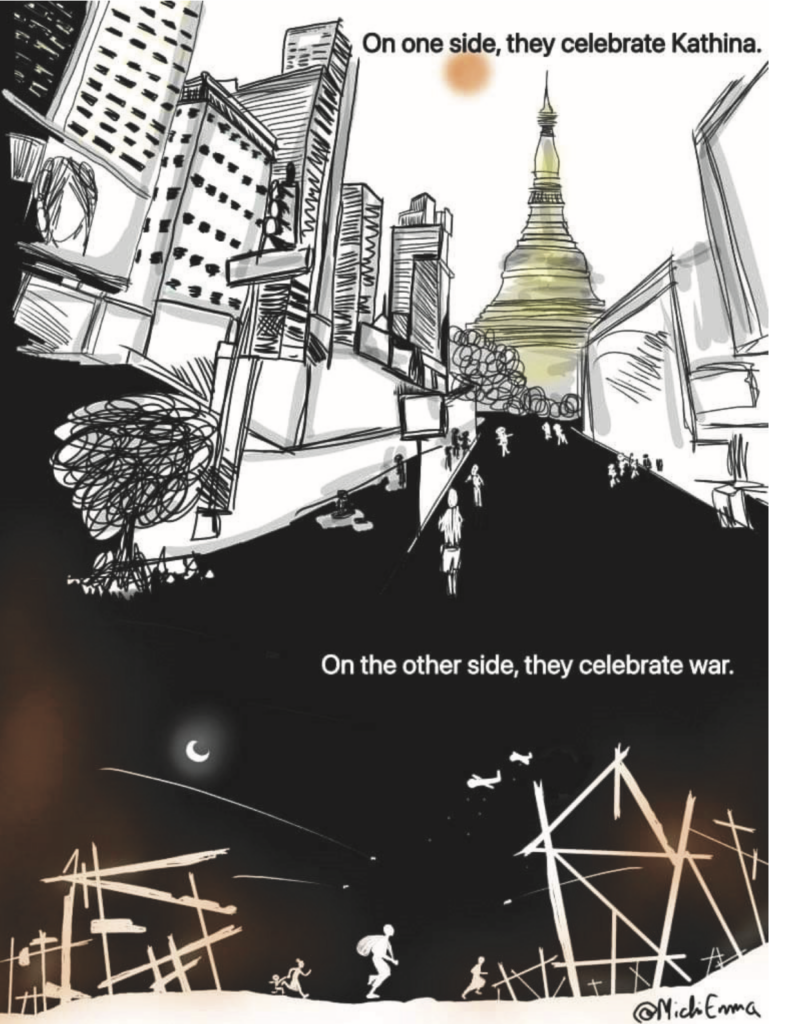

October 17 would have marked the festivities of Thadingyut in accordance with the full moon day of the Burmese lunar month, yet on this day people were forced to abandon their homes and flee the village.

The Festival of Lights symbolizes the return of the Buddha from the celestial realm. Celebrated at the end of Buddhist Lent after three months of fasting, markets bustle with foods, activities and gifts as devotees prepare to pay homage to the Buddha, his teachings and the monastic community. Thousands of oil lamps and candles are lit to illuminate pagodas and monasteries. In a serene atmosphere with processions through the streets, people carry lighted lamps to dispel ignorance and illuminate wisdom.

Kathina / Kathein is a Buddhist festival celebrated in Myanmar and neighbouring countries during which people offer new robes and objects to the monks. It spans the time between the full moon of Thadingyut to the full moon of Tazaungmone, usually in October or November according to the Burmese lunar calendar. The junta organised official celebrations of Kathein to portray the illusion of peace and prosperity, while its military massacred civilians across Myanmar.In a punitive and non-targeted strike against whoever they could find, the national military murdered six citizens in a now trademark display of brutal punishment meted out to those who might support democratic self-determination.

In the days following the massacre, some villagers returned, trying to reconstruct events and understand what happened during relatives’ final moments.

It was on October 18th that the military column moved on to Sai Pyin, and members of the People’s Defence Forces (PDF) were able to re-enter the village to inspect the scene.

They discovered two bodies near the monastery and one outside the village, all of whom had been shot. Three decapitated heads were displayed on a fence near the main road, with the headless bodies and other body parts abandoned recklessly nearby.

Of those killed by the military, three were shot, and a further three brutally dismembered.

Ko Myo* has shared details from his own journey. Also related to U Tin Hlaing, Ma Myint’s father, Ko Myo knows that U Tin Hlaing went toward the monastery, where he was involved in a standoff. The military were already there, confiscating possessions from the resident monk, including taking away his phone. Despite the monk’s protests that U Tin Hlaing were too old to trouble them, he did not survive.

U Tin Hlaing was one of three subjected to horrific acts of dismemberment. 40-year-old U Kyaung Po, and U Thet Aung faced similar fates. Soldiers decapitated and mutilated their bodies, cutting off their heads, hands, and other body parts.

Three heads were hung on the fence along the main road of the village.

The bodies without heads and some other body parts were found nearby.

They were brutally murdered. They chopped off the heads and hands, then cut open the chests and burned them.

Ko Myo’s uncle, seventy-year-old U Yar Sein was shot dead, as were U Htay Lwin, and the prisoner that the military had brought with them from elsewhere.

U Yar Sein had been sheltering at the nearby village of Ywah Shay, a nearby village, and had returned to Sipa in order to collect blankets, only to be shot by soldiers.

The military’s actions were in violent reprisal for a PDF attack that had occurred several weeks prior, on September 20th. The People’s Defence Force had engaged a military column of 80 soldiers near Sipa, capturing 50 of them, and killing 20.

Ko Myo speculated that the military’s actions in Budalin Township, including in Sipa, were meant to deter the PDFs from further resistance by instilling fear through violent reprisals.

We realized that they would come back for us, and that our village would likely be burned down since that battle occurred very close to our area. Some of the villagers had already moved food and goods to other places.

They did it to instill fear, but the people have become angrier and want to retaliate even more after these incidents.

These military attacks on Sipa are not in isolation. The military usually engages in acts such as burning down nearby villages and killing innocent civilians whenever they lose a battle.

Following an encounter on October 4th, the Northwestern Command’s soldiers began attacking villages, killing civilians and razing houses, according to the PDF.

On October 12th, soldiers killed six family members at a grocery store in Bandula Quarter, Budalin Township, including the 60-year-old owner, U Phoe Kyar, his 55-year-old wife Ma Mar Thin, their daughter and son, and two young nieces.

Around 11:30 AM that day, the military went to nearby villages such as Shan Tae and Myuak Kyi, arrested eight people, and killed half of them.

According to the Student Armed Forces (SAF), in the period October 4th to 22nd, at least 25 locals across Budalin Township were killed; 50 arrested; and over 400 homes burned.

The military column continued its rampage from Sipa to Sai Pyin, killing two more people before returning to Budalin on October 23rd.

A released captive reported that the Pyusawhti militias, affiliated with a radical patriotic monk named Wahthawa, played a significant role in the violence. The Pyusawhti are a loose network of pro-junta militias named after a legendary warrior-king who, royal chronicles say, founded the first Bamar empire of Bagan in the mid-9th century. The word Pyusawhti was earlier used for a rural defence force established by U Nu’s civilian government in 1956, according to a 2016 report on militias in Myanmar by the Asia Foundation, while militias under various names have played a crucial part in counter-insurgency operations since Myanmar’s independence in 1948.

The Pyusawhti were much worse than the soldiers. They were also heavily involved in burning down homes, murdering, and raping civilians.

The Pyusawhti militia have some form in the committing of such acts. Following a PDF assault on February 21st in Taze Township in which the bunkers of the Kanhtuma police station were burned down, the Pyusawhti and military forces retaliated by setting villages ablaze and killing residents.

Around 200 soldiers from KhaMaYa 708 (the Light Infantry Battalion 708), KhaLaYa 11 (the Infantry Battalion 11), and Pyusawhti militias entered one village after another, burning down homes and killing the villagers.

The dismembered bodies of 11 people were displayed in mockery. In the photos sent to MyaeLatt Athan, a head of a person was seen with a cigar in its mouth, with livers placed in front of that head. In another photo, sound boxes were positioned nearby, with cut pieces of legs leaning against them. They had cut open the abdomens of the victims, discarded the intestines, and mutilated the man’s penis.

In the aftermath of the military’s actions in Sipa, only about 20 houses remain out of the original 500, with the rest destroyed by fire. The village has been left deserted, and a funeral for the six slain men was held on October 27th.

Reflecting on the brutal acts and the loss of her aged father, Ma Myint expressed her anger toward the military’s actions against defenseless elders and civilians.

“What can the elderly and infirm do against them? If they think they can win this revolution by committing such murders, they may continue to kill as they wish. But they should never think that they will win.”

Testimony // In Ko Myo’s Own Words

My uncle and I had fled from Sipa, however, he went back to the village, thinking that the military hadn’t arrived yet, to bring us some blankets. He was arrested near the monastery. He was just a 70-year-old man who could not do anything.

They arrested everyone they saw. My uncle was shot dead along with another person near the monastery. I don’t think those two were tortured before they died as we didn’t find big wounds on their bodies. But the ones whose heads were cut off were different.

There were around 200 of them (soldiers). They separated into three groups and set fire to the village from every corner.

We already predicted that our village might be burned down because a battle had occurred nearby, so we moved some food and goods to safer places.

That’s what they do: destroy nearby villages after they lose a battle.

We didn’t just see the photos. We saw everything with our eyes. Three of them were brutally destroyed. They chopped off the heads and hands, cut the chests open and then set fire to them.

Many heads were separated from the bodies. They hung the heads and limbs on a fence. But the bodies were left in the yard. One of the bodies was mutilated; only the bones remained, as something had eaten it after it had rotted. The smell was horrific. The entrails were outside of the body, probably destroyed by dogs.

They tortured them before killing them. They even sliced off the face of one victim before chopping his head off. I have no idea how they can conduct such brutal acts against human beings. I heard some people saying they used some psychoactive drugs in order to be able to do commit these brutal acts.

I also thought that it was as a tongue in the mouth of a severed head when I first saw it. But it turned out to be his penis. They cut off his penis and put it in his mouth.

It was really brutal. They even cut the bodies open to traumatize the whole village so that we wouldn’t stand against them. They lost an entire column near our village, so they wanted to make an example of us: if we resist again, they’ll repeat this kind of cruel act.

But we hate them more than ever, rather than fearing them. They try to instill fear, but instead, we grow angrier and want revenge even more.

I have no idea why the PDF didn’t fight for us against the military while they were setting fire to the whole village. Why were they just watching without doing anything? I feel weak, not being able to do anything to respond while the soldiers of the military council were setting fire to the village.

Now we really need to consider what we should do if this kind of incident happens again in the future.

Our village didn’t have much strength left. When we destroyed the entire military column, we did it together with other revolutionary armed groups. After that battle, they took almost all the ammunition and weapons we had seized from the military. But it was our village that suffered the military’s revenge, and no one came to help us.

We returned to the village to assess the situation on October 19 and found that the bodies had been badly desecrated. We didn’t return on October 18 because some soldiers were still there until the 19th.

We first found my uncle’s body near the monastery and buried him there. However, in our village, there’s a doctrine that not even monks are allowed to be buried near a monastery. So we had to dig up his body again, move it to the cemetery, and bury him there.

U Tin Hlaing’s head was in the north. That’s him. He took care of us when we were very young. His daughter used to teach us when I was in the ninth or tenth grade. He lived not far from my home.

He was very old and walked slowly. He even had to use a walking stick just to walk. The soldiers were already there when he arrived at the monastery. Only one was a strong man among those six. The rest were very old. My uncle was 70 years old and also had to use a walking stick.

The severed head with the face sliced off – that’s Thet Aung. He was around 40.

I saw so much, that I will never have the courage to see again. I’ve never experienced such things in my life. I’ve seen the military killing locals by shooting before. But I had never seen anything like this one. This one was horrific.

We ask any armed groups: if you capture even one or two of those Pyusawhti, leave them for Sipa. We have something on our minds after our villagers were killed like this.

All names have been changed for safety reasons.

This article and this interview were first published in Burmese in Myaelatt Athan, the newspaper covering central Burma. It was written by journalists Thomas Lynn and Chal Yi. It was then adapted by our team: translation by SMR103, edit by Shwe Nakamwe and illustrations by Michi Emma.