Myanmar’s Stateless Migrant Children in Thailand

By Myo Thiha, Nathaphob Sungkate, Tin La Pyae Woon, Yamin Oo

In the suburbs of Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand, small communities of Myanmar migrant workers are staying in cramped rental households. Each family typically resides together in one small room, serving as a space for all daytime activities as well to sleeping. One such resident is Saw Win (pseudonym), who lives with his wife and three children.

Saw Win earns approximately 11,400 baht per month, with expenses including a 3,000-baht room rental fee and 8,000-9,000 baht for family meals. While he works for a large company not far from his residence, his wife takes care of the children and household chores. Their two eldest twin children meet the criteria for regular schooling and receive medical benefits.

However, Saw Win’s youngest daughter is rendered stateless as she did not receive notification of birth from Mueang Samut Sakhon District Office. “After my child was born in Samut Sakhon Hospital, I prepared all the documents and went to the district office. But the official said that I needed documents from the employer where I work so that they could issue a birth certificate”, said Saw Win.

For every child, a birth certificate is a crucial document for identity verification and nationality. Thailand recognizes the right to register births and the right to be legally acknowledged, as outlined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). This applies to all children, whether they are born to parents with legal status or are abandoned or stateless. It is the responsibility of the state to register births to affirm legal identity and prevent children from becoming stateless.

Despite multiple requests, Saw Win has never received the required documents from the company. According to him, the officials did not provide a reason for the inability to issue the documents.

Even though Saw Win is a legally employed migrant worker, he still cannot access the right to register the birth of his child. This situation raises questions about the birth registration process related to migrant workers’ factories/ workplaces and local government agencies in the area.

FIGHTING FOR A BIRTH CERTIFICATE

“The birth certificate is important for my child. It gives my child access to medical care for just 30 baht.”

Saw Win said that the birth certificate is essential to ensure that his child will receive basic care in Thailand, including health and education. The UNICEF Thailand’s report on Rights and Approaches to Facilitating the Acquisition of Legal Status for Migrant Children in Thailand states that once acknowledged as persons under the law of the Kingdom of Thailand, migrant and displaced children are entitled to various rights, including the right to reside in the Kingdom of Thailand, the right to work, the right to use/inherit a surname, the right to state welfare, the right to travel and move residence, the right to access justice, and the right to participate in expressions.

Saw Win compared the case of his daughter not receiving a birth certificate with the case of his twin children, who were born earlier and did receive birth certificates. This difference arises from the fact that his wife’s previous employer assisted in providing the necessary documentation.

“When the twins were born, my wife was working at a company. She received a certified document from her employer, enabling our children to obtain birth certificates.”

After giving birth to their first twin children, she decided to quit her job to take care of them. She gave birth to their youngest child in July 2020. “I spoke to the responsible person and her assistants (clerks) at the company multiple times, but they never clearly stated whether they would provide the necessary documents to register her birth, leading to us feeling hopeless. Other coworkers also faced the same issue, and no one received certification from the company.”

PHOTO // A group of motorcycle taxi drivers in front of Samut Sakhon Hospital, who assist migrant workers in registering births for a substantial commission.

While Saw Win tried to navigate this issue through standard procedures, other migrant workers opted to use the service of brokers, specifically a group of motorcycle taxi drivers in the area. By paying 3,000 Baht to this group of brokers, they would facilitate the issuance of birth certificates for the migrant labor community.

The company where Saw Win works was interviewed by our team on January 9, 2024. Regarding the information provided by the company, all its migrant workers are direct employees of the company, and therefore, migrant workers already have all the required documents, so they have legal rights, including the right to register the birth of their children.

The company’s representatives have acknowledged the issue and stated that an investigation into the case will be conducted. It is assumed that the problem may arise from communication gaps between the migrant workers and the human resources department.

When asked about the process of requesting documents from the employer, the company’s representatives emphasized that the issuance of documents falls under the normal organizational process. It is the responsibility of their human resources department when government agencies ask the workers for required documents to prove themselves as the company’s workers. They viewed it as not being such a burden preventing the organization from providing such documents to migrant workers.

“It is a normal corporate document issuance process,” said the company.

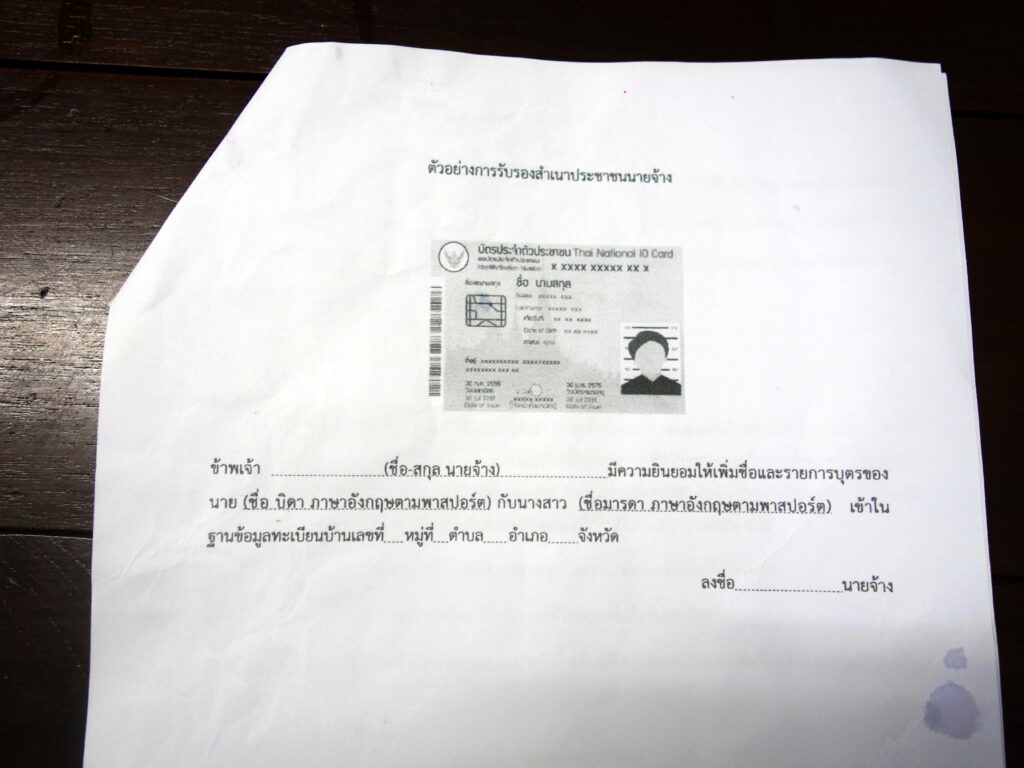

PHOTO // Example of a document showing consent to add the names and details of children of migrant workers’ children to the company’s household registration database. Saw Win has been assisted by an organization to help him drafting a request for documents from the employer certifying the birth of his child since March 20, 2023, but he has not received any response yet from the company where he works.

Moreover, when investigating the birth registration process for children who are not from Thai nationality, in the case of Saw Win’s daughter born in a hospital, the hospital issues a birth certificate. Parents then prepare the following documents:

1. Copy of house registration of the house owner (if any)

2. Identification card of the notifier

3. Hospital-issued birth certificate (if any)

4. Identity documents of the parents (if any), such as stateless ID cards for non- Thai nationals, passports, or border passes.

These documents are submitted to the district office to ensure accurate and lawful birth registration.

However, the real situation in Thailand is that despite the main policy adhering to the convention on children’s rights, requiring registration for all children born in the country, practical implementation varies. Many state officials in different areas do not consistently follow this policy.

PROBLEMS OF REGISTRATION

“The enforcement of having foreign laborers registered under employers’ household registration has led to issues, particularly when foreign workers give birth. In such cases, foreign workers often need to use their employer’s household registration for certifying births.”

Siwawong Sooktawee, who works at the Migrant Working Group and has over 20 years of experience in working at civil societies for labor rights of migrant workers and in assisting with the birth certification process, shared insights into the challenges faced by Saw Win. He questioned why, in many instances, workers still need documents from their employers.

However, according to Siwawong, the regulations from the Central Registration Office and The Civil Registration Act of 1992 state that it is not necessary to use documents from employers. In cases where foreign workers have passports, work permits, and other identification documents, these should be sufficient for birth registration.

Another perspective comes from Pakpoom Sawangkhum, an independent lawyer and former civil society worker on migrant labor issues. He provided information on November 30, 2023, addressing the problem of registering births for migrants’ children, referring to the article “Migrant Child Birth Registration: Regulations on Building Bridges or Barriers”:

“After the announcement of the regulations by the Central Registration Office regarding registration and identification cards of foreigners authorized to reside and work in the Kingdom in 2018, under Section 6, paragraph two, it was specified that “the address of migrant workers in the record should be the employer’s residence, factory, or workplace where the foreigner is employed or the residence provided by the employer, with confirmation from the employer as evidence.”

This situation has resulted in employers being considered as landlords of foreign laborers, leading foreign workers to need consent letters from employers for birth registration. Many employers, however, reject supporting such consent and personal documents, citing a lack of understanding of the registration system for non- Thai nationals, especially in large companies with a significant number of employees.

“The problem is that many government officials request more documents exceeding the fundamental requirements. Notification of birth sometimes requires the owner of the house to certify it and the host of the migrant worker is the employer. There are many cases where NGOs go to assist the migrant workers and talk to district officials about legal matters, then they issue a birth certificate,” Siwawong added.

Siwawong analyzed that the problem is caused by many reasons, including the use of discretion by officials beyond what is required by law, corruption by government officials, as well as the denial of responsibility by employers.

“The problem of not being able to access a birth certificate through our network is rare. But this is consistently encountered in every area, especially in border regions and areas with a significant population of foreign workers,” Siwawong concluded.

PHOTOS // Most migrant workers in the province come to Samut Sakhon government hospital for childbirth.

Ko Min Oo, a labor official from the Foundation for Education and Development (FED), an organization dedicated to assisting Myanmar citizens both domestically and internationally in securing basic rights, has expressed his views on this matter:

“The issue of employer certification is complex. Migrant workers are changing jobs or employers or moving to new places of work many times. However, their residence information remains with their previous employer, leading to difficulties when reporting births under the current employer’s residence address and contacting the previous employer for the workers who have already moved.”

The potential impacts of not having a birth certificate on children, as pointed out by Ko Min Oo, are multifaceted. Children may encounter difficulties when enrolling in school, as educational institutions typically require identity verification documents. The absence of birth certification can lead to statelessness, preventing them from returning to their home country. This situation also increases their vulnerability to human trafficking.

Regarding the lack of access to healthcare schemes, Saw Win mentioned that when his young child falls ill, he has to take her to a distant private hospital since they do not have the right to receive medical treatment at government hospitals. Additionally, there are expenses for transportation and medical care, amounting to more than 400- 500 baht per visit while his older twin children with birth certificates are entitled to pay only 30 baht for medical treatment.

Sompong Srakaew is the founder of the Labor Protection Network (LPN), an organization that works to improve the quality of life of migrant workers in the Samut Sakhon area and other areas in the ASEAN region. He states that the conditions imposed by the district and municipal authorities in Samut Sakhon are overly strict. In many cases in the Samut Sakhon area, government officials request the registration of the residence and addresses of the parents of the child when laborers are unable to provide these documents, making the birth registration process unsuccessful. This led to the emergence of a group of brokers who collected money from migrant workers, often stationed near municipal offices or district offices in exchange for processing documents.

“When it comes to policy, there shouldn’t be many conditions if the child is born there. Every child born in Thailand should be able to register their birth. However, at the local government level, each municipality imposes different conditions, resulting in children not having access to birth registration,” said Sompong from LPN.

CHILDREN AND POLICIES: BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE

“Every child, if proven to be born within the Kingdom of Thailand, should be able to register their birth. I believe it’s a matter that is not consistently practiced in compliance with regulations. And, it is not limited to any specific location; it occurs in many areas in Thailand.”

Venus Srisuk, former Deputy Director- General of the Department of Provincial Administration Registration Department, Ministry of Interior, Thailand,, who is currently retired from government service and serving as an advisor to the Ministry of Interior told the reporters that the law supports every person born within the Kingdom. According to him, every child has the legal right to birth registration based on their parents’ status.

“There is no need to use a certification from the employer because the regulations do not specify that documents from the employer must be used in the registration process. If a child is born in a hospital, the person responsible for notifying them is the hospital director.”

Venus added that when the hospital successfully delivers a newborn child, the hospital’s medical registry department will issue a hospital certificate of birth for the child. Parents can then use this document to apply for a birth certificate directly at the district office.

At the same time, the reporter has reached out to the registration department, Mueang Samut Sakhon District Administrative Office to inquire about the aforementioned information on such matters. “If migrant workers do not present documentation from their employer, it does not mean they cannot register the birth. It is just that the child’s name will be in the central household registration and when the child reaches the age of 5, his name needs to be listed in the regular household registration. Therefore, it necessitates the subsequent transfer to the employer’s household registration where the name of the father or mother is listed.”

The most common problem in the Samut Sakhon area is a lack of effective communication between migrant workers and officials. Therefore, it is necessary to rely on a middleman such as a motorcycle taxi group in the area or an employer as a middleman to help communicate.

In this regard, the registration department of the Mueang Samut Sakhon District Administrative Office claimed that children born at Samut Sakhon Hospital must register their birth at the Samut Sakhon Municipality Office in Thailand, not at the Mueang Samut Sakhon District Office.

The reporter visited the Samut Sakhon area and met with a worker from Unicorn Mahachai Company who had recently given birth at Mahachai Hospital on October 27, 2023. During the interview, the reporter asked about the process of requesting a birth certificate. It was revealed that, as the initial step, they need to prepare the following documents:

- Passport of the parent (father and mother);

- Childbirth record book (Document from the hospital);

- Letter of recommendation from the employer; and

- Documents translated into Thai.

After that, the migrant worker took all the documents to Samut Sakhon Municipality for document verification. The officer sent him back to get the document stamped at Samut Sakhon Hospital. The documents were then checked and he received his birth certificate back. However, the migrant worker stated that he did not know the process and that he needed to pay the broker 2,000 baht to help with the birth process this time.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimated that Thailand has approximately 500,000 migrant children under the age of 18. Among them, there are many children born in Thailand who have not yet registered their birth according to the law because of the gaps between the existing policy and implementation at the local level in various areas.

Siwawong Sooktawee estimated that approximately 10% of children of migrant workers (around 50,000 children), who arrived in and were born in Thailand, do not have legal birth registration documents.

Particularly regarding the documents that are required for birth registration, one of the main difficulties is requesting documents from the employer. The issues that arise not only affect the children and parents but also affect the stability of the country. As Venus Srisuk mentioned, human rights are a key element of national security.

Therefore, it is the responsibility of all parties, both the government and the private sectors, to collaborate in registering the births of migrant children. Birth registration provides essential data that allows the Thai government to comprehensively and efficiently manage and care for the entire population.

Legal birth registration also provides an opportunity for those children to be able to return to their country of origin. When there is no legally recognized birth certificate, these children may remain stranded in Thailand, without being able to contribute by studying or working legally.

“The refusal to proceed with the birth registration for migrant workers not only causes missed opportunities for Thailand but also contributes to the creation of stateless individuals in the kingdom. Birth registration benefits the state by providing clear information on the demographics, allowing the government to know which populations exist and where they are located,” concluded Venus.

After the reporter team talked with Saw Win’s company on January 9, 2024, it concluded that, due to the impossibility to disclose information of migrant workers to the company, the team made a request to the Labor Protection Network (LPN) to act as an intermediary assisting Saw Win’s case move forward.

However, birth registration for all children in Thailand still faces many problems and does not fully comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Thailand has signed and ratified these agreements, acknowledging that it is the responsibility of the state to ensure the registration of the birth of every child to ensure their legal identity and prevent them from becoming stateless.

What complicates this further is that the problem has less to do with the apathy of the Thai state than the web of corruption that has spun around the process of registering births. It must be noted, also, that though the Thai government has racked up a justifiably dubious reputation for repatriating migrants, even in the most extreme of circumstances, in recent months it has embarked on building shelters along its borders with Myanmar. Lieutenant General Prasarn Saengsirirak, commander of Thailand’s 3rd Army, has gone as far as to say that those crossing the border will receive humanitarian aid.

At one level, this is less a bilateral problem than an international one. Migration at a time of war and conflict cannot be restricted to borders, and cannot be reduced to problems of sovereignty. The international community cannot shut its eyes to the plight of these children, it cannot pretend that the problem does not exist. Relevant multilateral bodies and institutions, whose mandate it is to investigate these issues, must do so accordingly. It is they, they mainly, who can resolve the question of which State for the children of migrants.

A LONG EXODUS

Myanmar has been grappling with the consequences of a protracted civil war for several decades, forcing people from conflict-affected areas to abandon their homes and seek refuge in neighboring countries for their survival. Following the most recent military coup in February 2021, the uncertain political atmosphere, economic decline, and a lack of job opportunities resulted in an estimated 400,000 Myanmar citizens seeking employment abroad.

Thailand has become a home for many refugees from Myanmar. They face numerous problems and challenges crossing the border, to escape conflict and seek shelter in Thailand. For decades, Myanmar migrants form a significant and thriving community of their own in Thailand and the most important non-Thai workforce.

According to a report from December 2022 by the Office of Foreign Workers Administration, Department of Employment, Ministry of Labor, Thailand, there are nearly 2 million migrant workers from Myanmar in Thailand, and a vastly underreported substantial number of Myanmar nationals are entering and staying in the country without holding the required legal documents.

For these foreign workers from Myanmar, they face challenges in seeking benefits from employers and experience a loss of labor rights. Despite these difficulties, considering the political situation in Myanmar, returning home is extremely risky. The only viable option for these individuals, particularly those currently working in Thailand, is to strive for survival for themselves and their families remaining in Myanmar.

This Report was Produced with the Support of The Thai-Myanmar Media Fellowship 2023 organized by Visual Rebellion Myanmar and the Spirit in Education Movement (SEM)

A version published in Factum (Sri Lanka) was reviewed by Dr Ranga Kalansooriya, Ph.D and Uditha Devapriya of Factum.

A version in Burmese was published by Dawei Watch and a version in Thai was published in Thairath.

A Month of Unity for Burmese and Thai Workers

One river, one border, two realities

Workers Demand Labor Rights For All In Thailand

ELECTION VOX POP // Thai and Myanmar residents hope for a common fair future

The Men Fighting for Karen Rights in Thai Politics

Myanmar diaspora hopes for a new dawn as Thailand votes to shed its green uniform

Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand not invited to first social security board election

Into the Life of Myanmar Women Factory Workers