Myanmar people reject sham elections by war-criminal junta

Millions of citizens are calling for a boycott of the sham vote orchestrated by General Min Aung Hlaing’s regime, which controls barely half of the country. In their thirst for legitimacy and cash, the military hopes to persuade other nations to normalize relations.

Reporting & Writing by Josephine Kyi and Nyo // Editing by Shwe Zin Soe

YANGON / RAKHINE / SAGAING // “When is the vote? Will I be arrested if I don’t participate?” asks sixty-year old Ma Shwe. This is in stark contrast to the two previous elections in 2015 and 2020, during which an enthusiastic electorate voted almost unanimously for the National League for Democracy (NLD). All members of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party are either on the run or in prison since the coup on February 1, 2021, the day the newly elected parliament was due to convene for its inaugural session.

The military junta, renamed the State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC), has announced that elections will be held in three phases, based on the Indian model: on December 28, 2025, then on January 11 and 25, 2026. In total, nearly 5,000 candidates and around 50 parties have been authorized to run. The bustle does little to hide the scam: all opposition parties are excluded from the ballot, there is no sign of life from Aung San Suu Kyi according to her son, and pro-military parties need only 35 seats to control Parliament.

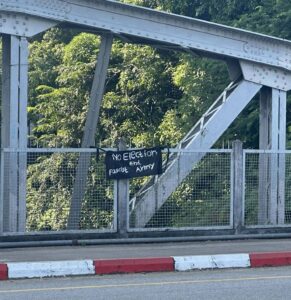

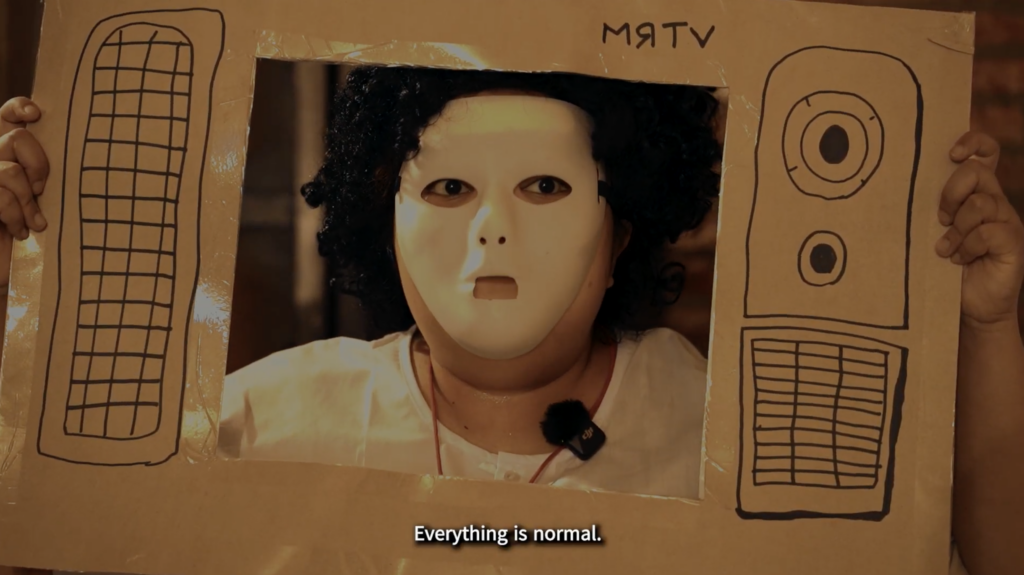

Via the website “No To Sham Elections,” nearly 1.8 million Internet users have expressed outrage at these rigged elections. In the regime-run embassies and consulates, in Taipei or Chiang Mai, the diaspora voted with their feet, by not going, except for families linked to the military. Across Thailand, Rangoon Radio interviewed migrant workers under anonymity. All say that the poll is “utterly meaningless“, “absolutely shouldn’t happen” and will do nothing to address their daily struggles. In the satirical sitcom Safe House Stories , young actors living on the Thai-Myanmar border choose humor and Yangon slang to highlight this popular defiance.

Those who still live in Myanmar find it more difficult to escape the pressure. The Rangoon Scout Network (RSN), which alerts residents to upcoming attacks, explains: “They collected the electoral rolls and posted them on the notice boards of ward administrative offices. Citizens who did not show up at their respective offices to validate their registration received a visit at home. Residents destroyed at least ten election notice boards, but military motorcycles with sidecars are now patrolling the streets to deter sabotage.“

As on every December 10th since the return of the dictatorship, the streets of major cities emptied in a “Silent Strike” to mark International Human Rights Day. A week earlier, a handful of activists led by Dr. Tayzar San, a leading anti-coup figure, organized a flash demonstration in Mandalay, the country’s second-largest city. Those few minutes spent throwing flyers into the air and chanting slogans for “the release of political prisoners, the boycott of elections and the end of forced conscription into the army,” cost one of them his freedom. Htet Myat Aung, a 24-year-old student unionist, was imprisoned under a new draconian law.

Hundreds of people have already been charged for actions on the ground or online criticism under the “Law on the Protection of Multiparty Democratic General Elections from Obstruction, Interference, and Destruction.” The Ministry of Information boasts of having arrested famous artists, but the electoral commission has also admitted that in 56 of the country’s 330 municipalities, it will not be able to organize the election. After five years of what is considered the most fragmented conflict in the world, involving more than 1,200 armed groups, entire regions are beyond central control.

In the coastal state of Rakhine, the Arakan Army (AA) controls the countryside and defends the interests of Buddhist Arakanese, the majority ethnic group. The AA is fighting a fierce battle for complete autonomy in this strategic territory of the Indian subcontinent, which it already administers de facto through the issuance of visas and the establishment of courts. Holed up in Nay Pyi Daw, the junta has only been able to organize elections in three urban centers there. U Myo Kyaw, secretary general of another party campaigning for self-determination, said: “Even in these three districts, the regime has not been able to open polling stations everywhere. No one is interested in the whole thing. Their candidates are having great difficulty campaigning. I don’t know how they will be able to carry out their duties in Parliament or even how they will get there, given that transport has been disrupted throughout the state.”

The political veteran highlights the complexity of the mixed voting system: “All representatives in the lower house will be elected by a First-Past-The-Post system, but for the upper house and regional parliaments, half of the seats will be allocated by proportional representation. The whole confusing electoral process is designed to mislead the public.”

The UN also warns of the risk of using electronic voting machines without the option of casting a blank or invalid vote. These machines, which are limited in number, will travel and record data across the country, which has become a laboratory of authoritarianism in the 21st century. The identification of opponents is also facilitated by an artificial intelligence-based surveillance system at the heart of the military crackdown.

“No one can guarantee their safety,” says U Myo Kyaw of potential dissenters in areas controlled by the regime. “Although voting is legally optional, abstaining is a great risk for people monitored by the regime’s henchmen or living near polling stations,” confirms the scout network.

Ma Ei, a nurse involved in the civil disobedience movement, believes that "the priority is the safety of these people. For those in areas not controlled by the regime, I urge them to oppose this election.” She operates from the central Sagaing region, a hotspot for anti-regime protests, which has been brutalized by daily airstrikes and ground offensives. Since the coup, thousands of residents have lost loved ones - and so many children - lived in darkness, and fled their burned homes.

Guerilla Grass theatre group released “The Puppet’s Ballot“, a powerful performance about the grief of losing a loved one, about a dream of the future that can never be replaced. “How far apart is a ballot box from a crater left by a bomb? Is the value of a vote equal to a lost life, or the worth of a family dinner table that is no longer whole?”

Bae Gee, a local scout leader, describes yet another ignominy “We saw soldiers attacking 20 villages in the Yin Mar Bin district. Then they carried furniture out of civilians’ homes to the Northwest Regional Military Command (NRMC) on the other side of the stream, while firing shots indiscriminately.“ An early voting station has been set up at this base: ”Voting is strongly encouraged in areas close to the NRMC and under regime control. Soldiers also helped some villagers with their farm work, food, and basic medical assistance to encourage them to vote.” Meanwhile, attacks by fighter jets and paramotors armed with machine guns are intensifying, particularly in areas affected by the first phase of voting, according to Bae Gee. “They are rushing to clear the area so that this can happen. We should not be concerned about whether the elections are going well or not. I am more concerned about the air strikes, which will continue regardless.”

Many organizations are demanding an embargo on the sale of aviation fuel to the Burmese military to stop its desperate strategy of submission from the air. The junta’s largest source of cash is the offshore oil and gas field managed by the junta-owned Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE), and its revenue source is the Thai company PTT, which buys its output. Financial reports show that the junta netted nearly US$240 million during the first three years post-coup from MOGE. This is the money used to import the aviation fuel for the air terror bombing campaign and buy drones and other war technologies.

In December, 30 people were killed and 70 wounded in the bombing of a public hospital in Rakhine, the deadliest attack on a health facility since the coup. Despite these war crimes, the junta is securing international support, knowing that governments are content with the slightest crumb of democratic exercise to reopen dialogue. Cambodia, Vietnam, Russia, China, Belarus, India, Kazakhstan, Japan and Nicaragua have sent observers, effectively giving their seal of approval to the regime’s organization of the election.

The Ministry of Information recently launched platforms promoting the army’s political strategy, such as Myanmar Narrative. Min Aung Hlaing, the coup leader, army chief, and prime ministerial candidate, has increased his trips abroad, particularly after the powerful earthquake in Sagaing last March. Millions of people were surviving amid the rubble of the earthquake and the ruins of the conflict, but the junta attempted to capture the world’s attention with a “peace forum” in its capital.

In August, the army hired two lobbying firms linked to the US Republican Party to improve its relations with the West. After imposing 40% import tax on Myanmar, Donald Trump expressed interest in its rare earths, currently being sold off to the highest bidder and least scrutinized by militias controlling the resource-rich northeast.

In the wake of this exchange over trade tariff, US sanctions imposed on certain allies of the generals and army conglomerates were lifted. Then the temporary protected status of Burmese citizens in the US was suspended, on the grounds that they could now return home safely, citing the upcoming elections as a sign of improvement. This decision affects around 4,000 beneficiaries who must find other legal avenues or risk deportation on January 26, 2026, the day after the scheduled end of elections in their home country. In the meantime, deportations of convicted criminals of Burmese origin have accelerated. Zaw Min Tun, spokesman for the military junta, said that “all citizens abroad are welcome to return to participate in the vote.”

U Myo Kyaw, an LDA politician, calls on other nations to reject the old-weary trap of fraudulent elections manipulated by ultra-authoritarian and violent actors: “The army must leave the political arena, focus solely on defense, and open up to ethnic autonomy. National unity must be built with representatives from each sovereign state. That is the only way to build a federation.” Meanwhile, more than two million people are on the brink of starvation in his native Rakhine. “People have left the cities because of the war. Some have gone to Yangon, others to rural areas controlled by the resistance. There is nothing to hope for from these elections, which are neither free nor fair. We have had many in our history, but none have been so chaotic.”