Myanmar’s Rare Earth: Profit, Poison and Power

Text & Interviews by Josephine Chyi & Shwe Zin Soe // Edit & Maps by Shwe Nakamwe

MONG PAUK, WA STATE – Rare earth elements (REEs), packed in white bags and loaded onto heavy trucks, roll out of Mong Pauk’s production zones under tight control. They pass military junta checkpoints before heading toward the official China–Myanmar border gate – a reminder that every sack of REEs leaving Wa State moves under the shadow of both the military junta and the United Wa State Army (UWSA), China’s long-term partner.

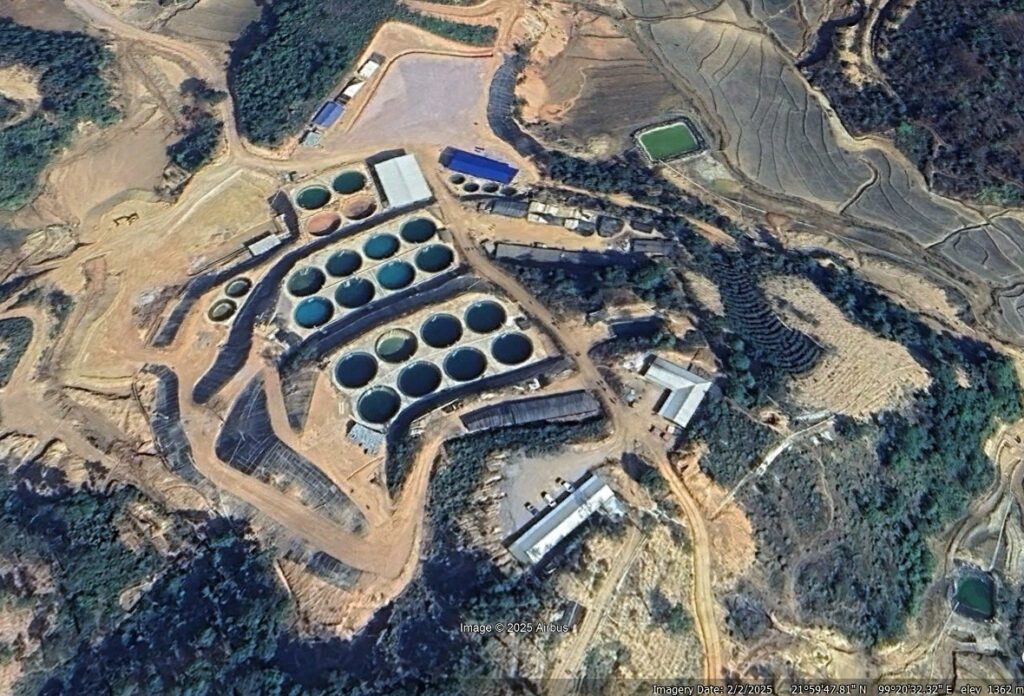

Currently, REE production sites in Myanmar are concentrated in Kachin State and Shan State, both located along the frontier with China. From satellite images, telltale rows of circular pools are now visible across the hills around Mong Pauk, the largest city in Wa State. These pools are the unmistakable signatures of in-situ leaching (ISL), the controversial process by which REEs are extracted. They now proliferate across the countryside, reshaping entire mountain ridges. REE production sites in Mong Pauk, have multiplied from three to twenty-six over the past decade, according to satellite monitoring by the Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF).

After ISL destroyed entire areas, the technic is still permitted in China, but it is now governed by an official production quota, a strict set of standards and an environmental impact assessment process that includes measures to mitigate against acid leakage. No one seem to be in a position or willing to uphold such regulations in Myanmar, where most operations have moved.

According to ISP Myanmar report published in July 2025, about 200,000 tonnes of rare earth have been exported from unregulated mines in Myanmar to China processing facilities between 2017 to 2024, including 170,000 tons during the post-coup period. “Imports of heavy rare earth oxides from Myanmar to China skyrocketed from their previous highs of 19,500 tons in 2021 to reach 41,700 tonnes in 2023-more than double China’s own quota for domestic HREE mining” according to a Global witness Myanmar report published in May 2024.

The report focused on the Heavy rare earth elements (HREE) production sites in Kachin state. HREE are seven minerals known for their higher atomic mass and sit at the core of the ‘green energy’ transition, as they are used for magnets in electric vehicles and wind turbines worldwide, magnets with unmatched magnetic properties. Today, China holds a near-monopoly on the refining and transformation of rare earths into magnets. Since HREE production especially is among the most environmentally destructive forms of mining, strict environmental standards are normally required.

Photos and videos circulating on social media show REE workers in Myanmar handling acids and chemical solutions in everyday clothes – often no more than plastic gloves and rubber boots – with no protective suits, goggles, or respirators.

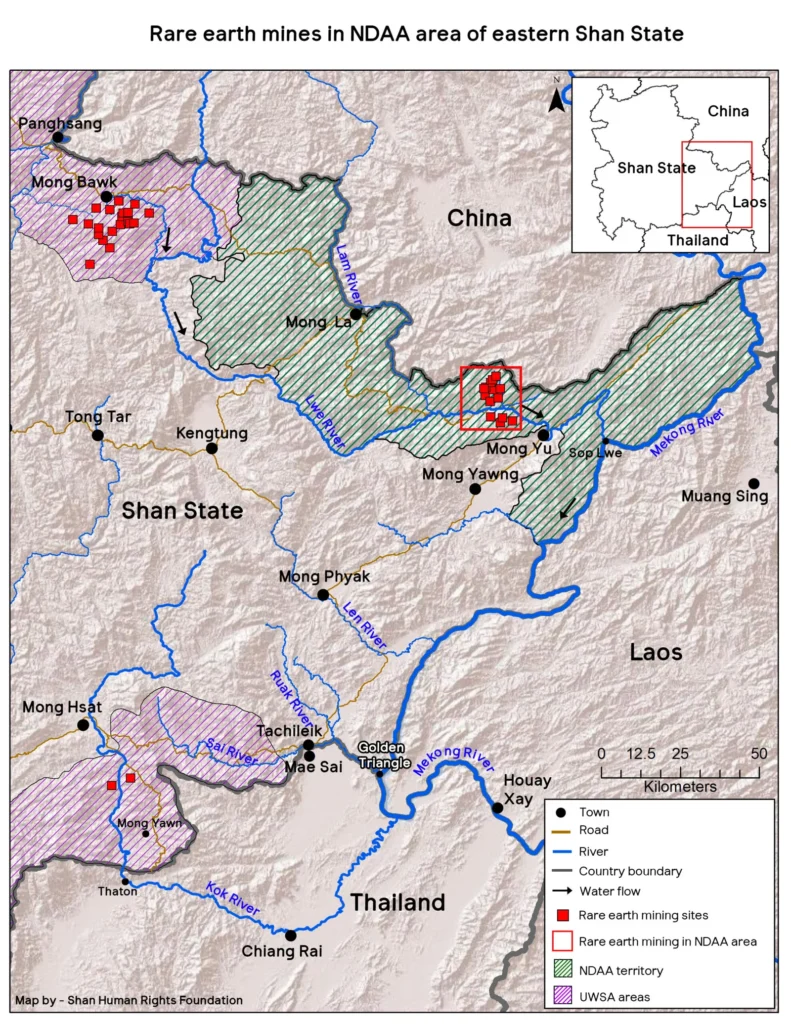

SHRF revealed the location of another nineteen new REE mining sites around Mong Yawng, a township in easternmost Shan State that is part of Special Region 4 and less than forty kilometers from the Mekong river and the Thai border. The hilly territory is under the control of the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA or “Mong La” army, as their headquarters are situated in this important trade town to China), since it signed a ceasefire with the Myanmar military in 1989.

Meanwhile, the UWSA announced in August 2025 that it would no longer provide military or economic aid to allied resistance groups, siding effectively with the increasingly China-backed junta. The powerful armed group did not answer questions from Visual Rebellion about its role in REE production in Mong Pauk and Mong Hsat townships. Wa remains entirely under UWSA control, where a functioning governance system exists, and – unlike Kachin – it is not an active battlefield.

In contrast to the surge in rare earth activity in Shan State, production sites in Kachin State’s Panwa and Chipwi have been impacted since late 2024, after the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) seized control from the junta-aligned Kachin Border Guard Force (New Democratic Army- Kachin).

According to a Global Witness report published in 2023, the number of mining sites in Panwa and Chipwi leapt to over 300 – a more than 40 percent increase between 2021 and 2023. Before the KIA takeover, Kachin’s REE sites had been controlled by the Border Guard Force, with profits funelled directly into military budgets. Workers and rights groups reported cases of sexual harassment of local women at the mines, but with no functioning governance system, perpetrators faced no consequences.

Since October 2024, the KIA has imposed new taxes on rare earths: a fixed rate of 35,000 yuan per tonne, or a 20 percent volumetric export tax. At the same time, KIA leaders have begun exploring international partnerships to reduce reliance on China. Reuters reported that in December 2024, Kachin representatives held an online meeting with an Indian delegation, and in July 2025 presented rare earth access proposals to the US government.

As companies are fumbling over deals on an unstable frontline, people in Kachin State are facing forced displacement, airstrikes, trade barriers, transportation disruptions, and worse phone and internet cutoffs than before the 2021 coup. These conditions have caused local businesses to collapse, big companies to leave, brain drain, physical and social insecurity, dependency, and fewer job opportunities for locals.

Wa State is not currently a conflict zone like Kachin State. The relative quiet in Mong Pauk began after the crackdown on online scamming along the China border, following the fall of Laukkai. And migrant workers who once relied on Kachin’s mines are now seeking jobs in Wa State.

One Shan worker described moving from Kachin to Mong La area, where the company that hired him exported thirty to forty truckloads of rare earths a year. Each ten-wheeler carried around 800 bags. “I heard news that the quality is good here,” he said, adding that as an experienced worker he earned 5,000 to 6,000 yuan (USD 700-840) per month – more than in Kachin. He estimated that each 50 kg bag was worth 20,000 yuan (USD 2800) meaning a single truckload could fetch about USD 2.24 million per truck, or between USD 67 and 90 million per year for his company. In the sole area where he is working and living on-site, the Shan worker, who wishes to remain anonymous, estimates that 10-15 companies are operating.

Job agents working between Chinese employers and local Myanmar employees advertise vacancies in Shan State over TikTok or Facebook which are the most used social media platforms in Myanmar. TikTok, more accessible in China than Facebook, is the preferred platform at the Myanmar-China border.

Mong Pauk is already a crowded city saturated by online scamming, nightlife, and mining of not only REEs but also other minerals such as tin. Mining is one of the major businesses of the Wa State economy and Mong Pauk is popular among workers seeking high-salary opportunities in northern Myanmar. There are large buildings housing gambling halls, KTV lounges, massage spas, hotels, Chinese restaurants, and mining industries in Mong Pauk city. These businesses mostly employ Myanmar locals in entry-level positions. Positions include cooks, masseuses, online scammers, nail beauticians, hotel workers, card players, and miners. Job vacancies for KTV, sex work, massage spas, and mining are still increasing on Telegram and TikTok, where Mong Pauk recruitment is most active.

For most jobs in Shan state’s sites, salaries paid are higher than those in Yangon, Myanmar’s commercial city. Even the daily wage of labourers clearing sites of trees and plants is ninety thousand kyat — about eighteen times higher than the official minimum daily wage of 6,800 kyat (USD 3) in Yangon. But the jobs expose workers to chemical hazards in difficult, mountainous terrain, often without being informed about the inherent health risks.

Women workers in water-monitoring positions in the mining area can make around 1,700 yuan (USD 237), according to a vacancy announcement by a job agent recruiting employees for mine production in Mong Pauk. Another post from early 2025 advertised 40 vacant jobs for “men under 40 yo“, specifying that a group of nine men are already leaving for the mining sites on February 13th.

According to a worker who has experience in a REE production site in a nearby area, a general worker earned three to four thousand yuan (USD 418-558) at his site. As he could communicate with Chinese technicians and was already familiar with REE production tasks from his previous job at a site in Kachin State, he was paid twice more.

Areas controlled by the UWSA, including Mong Pauk, use the Chinese yuan and Chinese language as official standards. Some workplaces in Mong Pauk even follow Chinese working hours. One of the main qualifications for many vacancies is Chinese language proficiency for communication with Chinese supervisors.

Women can find high-paying jobs in entertainment venues, while mining areas offer salaries well above national averages. Employment remains active but sharply divided along gender lines: men are concentrated in heavy labour, while women are more often hired for cooking and water-monitoring roles.

Many migrants from other regions of Myanmar are flocking there due to rapid decline in job opportunities elsewhere that has been caused by insecurity, conflict, and conscription since the coup of 2021. But residents from Mong Pauk are mostly left out by job opportunities in this new booming industry.

“They don’t trust the locals. Locals could sabotage production sites or reveal what is happening to outside media as they have a link to the land,” said Ko Sai Hor Hseng, SHRF spokesperson. “People here have no rights to any natural resource extraction. In fact, I think any kind of natural resources or business should be stopped right now. This is a terrible time for ordinary people, who are already dealing with the coup and ongoing conflicts. With governance collapsing, projects are pushed through in secret, without public knowledge or consent, leaving communities shut out and vulnerable.”

After a site is exploited and depleted, the soil is damaged for generations and companies simply moved out to another place. In the world power game, other countries in the region tried to position themselves as alternative sources of supply such as Laos or to upgrade as “strategic processing hub with future mining ambitions” such as Malaysia.

As for now, Mong Pauk remains the dominant centre of Myanmar’s rare earth industry – a city where mining, scamming, and nightlife converge, and where Chinese capital and Wa State authority operate in tandem. In Kachin, production is stalled but geopolitics are shifting, with the KIA attempting to court international partners. In Shan, production continues apace under UWSA and NDAA control, even as environmental damage mounts. For workers, rare earths bring both opportunity and exploitation: temporary high wages, but long-term toxic exposure, gendered risks, and dependence on armed groups. For communities downstream, each flood and landslide now threatens not only homes but also their health. Myanmar’s rare earths have become a global bargaining chip – but inside the country, they remain a local poison.

Ko Sai, spokesperson for the Shan Human Rights Foundation, warned that those in power must be held accountable: “Authorities must listen to local people and protect society. They are part of this society too.”

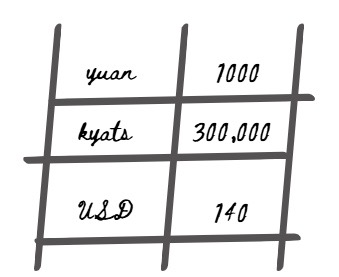

(left) Rice terraces sit next to chemical ponds used for rare earth extraction, raising contamination fears. [@Shwe Nakamwe / Visual Rebellion / Google Maps ] // (right) Conversion rates used in this article.