Airtrikes Epidemic (III) // “Not every house has a bomb shelter yet”

Children in the villages would watch helicopters fly overhead whenever they heard the sound. They would get excited, and even debate what type of aircraft it was. However, the situation has now changed.

At around 3:30 PM, November 10, 2023, rapid gunfire covered the village of Min Hla, the previously tranquil setting suddenly echoing with the crackling sounds of an aerial attack. It lasted fifteen minutes. A military helicopter dropped two 225kg bombs on the school and the monastery during the airstrike. It was a Friday. School had started as usual, with approximately 300 students and teachers present. By a sheer stroke of luck, however, on that particular day the school dismissed students 30 minutes early, due to a meeting scheduled to take place. No one was in school when the airstrike happened.

It was a Friday. School had started as usual, with approximately 300 students and teachers present. By a sheer stroke of luck, however, on that particular day the school dismissed students 30 minutes early, due to a meeting scheduled to take place. No one was in school when the airstrike happened.

“If it had happened while students were in the classroom, almost everyone would have been dead or got injured” said Ko Kaung Kaung.

Ko Kaung Kaung is a member of a local revolutionary team, Youths for Community. He was in a nearby village when the airstrike occurred. After the attack, he rushed to Min Hla in order to hear from people present about just what had taken place.

There was only a narrow path separating the school and monastery. Some classrooms and a temple within the monastery had been destroyed during the airstrike. But no one had been injured. The villagers of Min Hla who were caught off-guard by the airstrike were now on high alert, preparing bomb shelters in preparation for future attacks.

“Before the airstrike, there were no bomb shelters in the village. However, following these November events, people began constructing bomb shelters or bunkers within their compounds,” stated Ko Kaung Kaung.

Min Hla, home to 300 houses and approximately 2000 residents, is located in the Sagaing Region, about 120 kilometres southwest of Mandalay. The village was under the control of the People’s Defence Forces (PDF). Ko Kaung Kaung estimates that 65% of the village’s houses have built bomb shelters.

“Not every house has a bomb shelter yet. This is because some people do not have enough land on their property to accommodate a bomb shelter. Some neighbours have combined their land to construct a bomb shelter because they lack sufficient land area on their own.”

The cost of building a bomb shelter ranges between 300,000 and 350,000 Myanmar Kyat (MMK). This can vary depending on the quantity of sand, brick, and wood used. The locals of Min Hla faced additional challenges in collecting enough wood to cover the pits they dug.

“It’s fine with the digging process, but for securing the pit, hardwood is needed, and that’s the problem. It’s mostly only softwood available in our region, and it’s difficult to get good hardwood,” said Ko Kaung Kaung.

It’s not only civilians from Min Hla constructing bomb shelters – it has become a regional trend. The Sagaing Region has been subject to the most aerial attacks since the coup began (see box below). Regionwide, bunkers and trenches are also proliferating. The National Unity Government’s Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management issued a statement announcing their support for the construction of 730 bomb shelters to safeguard against airstrikes and artillery bombardment during the year of 2023.

The 15-minute-long airstrike that occurred in Min Hla continues to instill fear in the people. The villagers are afraid to resume their normal lives. The sound of helicopters still terrifies them. Children in classrooms rush to their teachers seeking help, while those at home hurry to their parents, some even cry. They can’t feel at ease until well after the sounds of helicopters fade away.

“For now, rather than watching the helicopter as they did before, children run to their guardians and call for help when they hear the helicopter,” said Ko Kaung Kaung. Adults similarly experience fear when helicopters fly overhead. They cease all activity, look for loved ones, and seek shelter promptly.

“There is already a bomb shelter in our yard, and as far as I know, there’s one in almost every house in our village. These shelters are crucial as they are the only ones we can rely on if an airstrike occurs,” according to U Phyu*, a resident of Paungbyin township to the north.

A month after another attack on Min Hla, on December 16, 2023, the Myanmar Army bombed U Phyu’s village, located in Paungbyin. He experienced the ordeal firsthand.

“It happened very close to us. Jet fighters appeared out of nowhere – we didn’t have time to flee.”

During the attack, a 3-year-old girl was killed, and a 12-year-old girl was injured. Several buildings and houses were destroyed. At roughly the same time during the third week in November, the People’s Defence Forces seized control of the town of Shwe Pyi Aye in the Sagaing Region. Following this takeover, the Myanmar Army conducted aerial attacks using helicopters and jet fighters.

Those who have encountered airstrikes report experiencing feelings of anxiety, fear, fright, and insecurity upon hearing helicopters or fighter jets. “In the minds of civilians and especially children, there exists trauma regarding the helicopters and fighter jets,” explained Ko Kaung Kaung.

U Tun Naing, a 38-year-old man from Kanbalu Township, has experienced airstrikes over ten times. “When military aircraft appear, everyone becomes terrified and takes refuge in the trenches. It’s a fear of death.”

Once, while tending to his herd of cattle in a grazing area, a bomb dropped from a helicopter nearby, and he had to crawl on the ground. In the resulting explosion he was unable to consider the lives of his cattle, only to save himself. A member of the PDF from Ye-U township cautioned locals to locate or prepare refuge areas as the military might conduct an airstrike at any moment.

“You must constantly search for nearby shelters upon hearing fighter jets, as their targets are unpredictable. Thus, you must always find a hiding place,” he advised.

Having encountered airstrikes multiple times, he has also experienced them while riding a motorbike and driving a car. In these situations, he had to stop his vehicle wherever he was and seek out a large tree for safety.

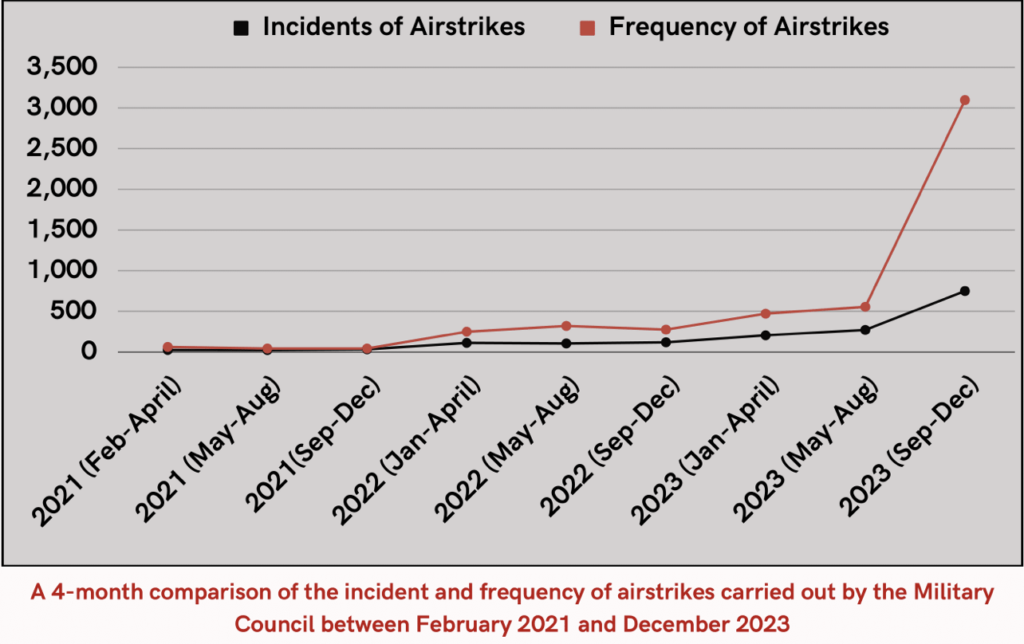

The military’s use of aircraft as a strategic asset and its targeting of civilians has become increasingly frequent since mid-2022, as reported by Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica.

On the other hand, PDFs are offering courses on how to prepare for airstrikes, and sharing instructions on what you can do to reduce the probability of harm eventuating from an airstrike. Everyone has been advised them to build a bomb shelter in their yard.

“We are offering the courses such as constructing bomb shelters technically, and how to stay safe during airstrikes, including knowledge about land mines and dangerous remnants after battle,” said Ko Zaw Tun, a member of Pale’s public administration.

Bomb shelters which used to be found only in the ethnic areas are now located everywhere in central Myanmar such as Sagaing and Magway Region.

As the duration of the coup d’état extends, it is of utmost importance to provide assistance for civilians facing the consequences and side effects of war.

It is really important to do operations very carefully to avoid hurting people in the area, no matter if they’re done by politicians or revolutionaries, according to Ko Kaung Kaung.

“We can’t just conduct operations. We also need to minimize harm to innocent civilians as much as possible.”

Visual Rebellion acknowledges that the airstrikes referred to in this article are not representative of the whole picture – it is much larger. For regularly updated information on airstrikes, please visit Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica and read the box below. The following information has been shared directly with Visual Rebellion by people who want their stories told, despite the dangers they face in sharing them. Names have been changed.

EVERY DAY, DEATH FROM THE SKY

On September 16, 2022, the Tatmadaw deployed helicopters to attack on a school situated in Let Yet Kone, Tabayin Township, Sagaing Region.

The military’s assault was conducted both from the air and on the ground. The aerial attack resulted in the deaths of five students, while seven students lost their lives during the ground assault, bringing the total casualties to 12. (see our story)

Resulting in the deaths of more than ten individuals, this attack on civilians meets the criteria for of a massacre. Sadly, there are many more.

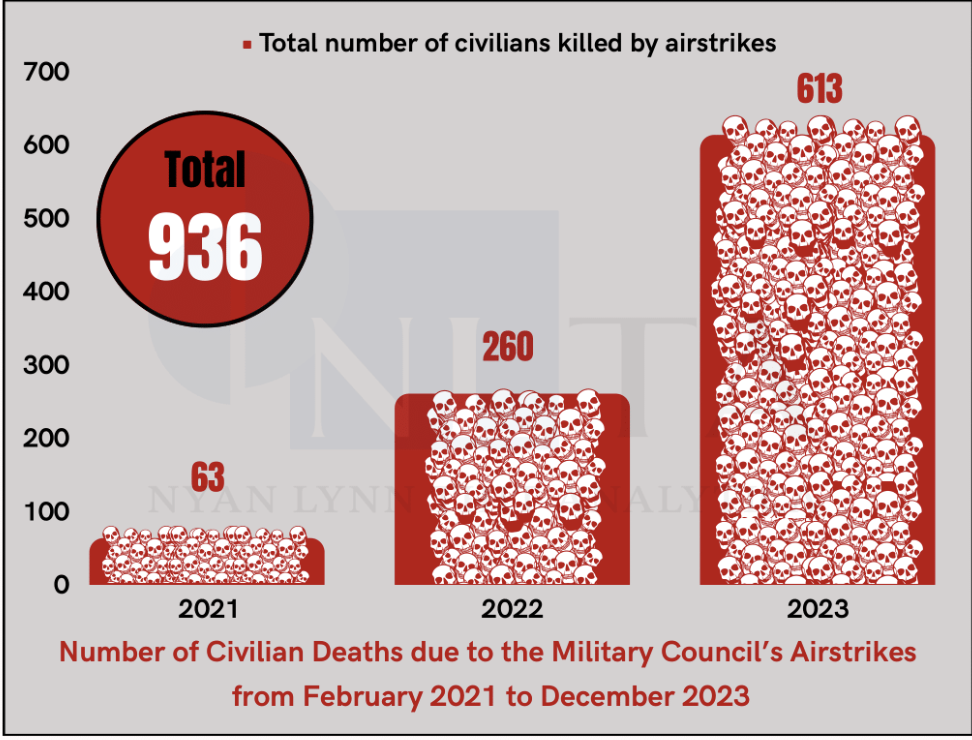

In the three years following the coup, the Myanmar military has conducted 1,652 airstrikes across the country. A report by Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica has record the deaths of 936 civilians, with another 878 injured. 241 houses, schools, hospitals, clinics, and religious institutions were destroyed as a result.

In 2021, there were 85 airstrikes nationwide resulting in 63 deaths, 42 injuries, and the destruction of 19 buildings.

In 2022, the number rose to 339 airstrikes, leading to 260 deaths, 85 injuries, and 41 buildings destroyed.

In 2023, the situation escalated further with 1,228 airstrikes, resulting in 613 deaths, 751 injuries, and 181 buildings destroyed. It is evident from the statistics mentioned above that the aerial assaults by the Myanmar military have increased year by year.

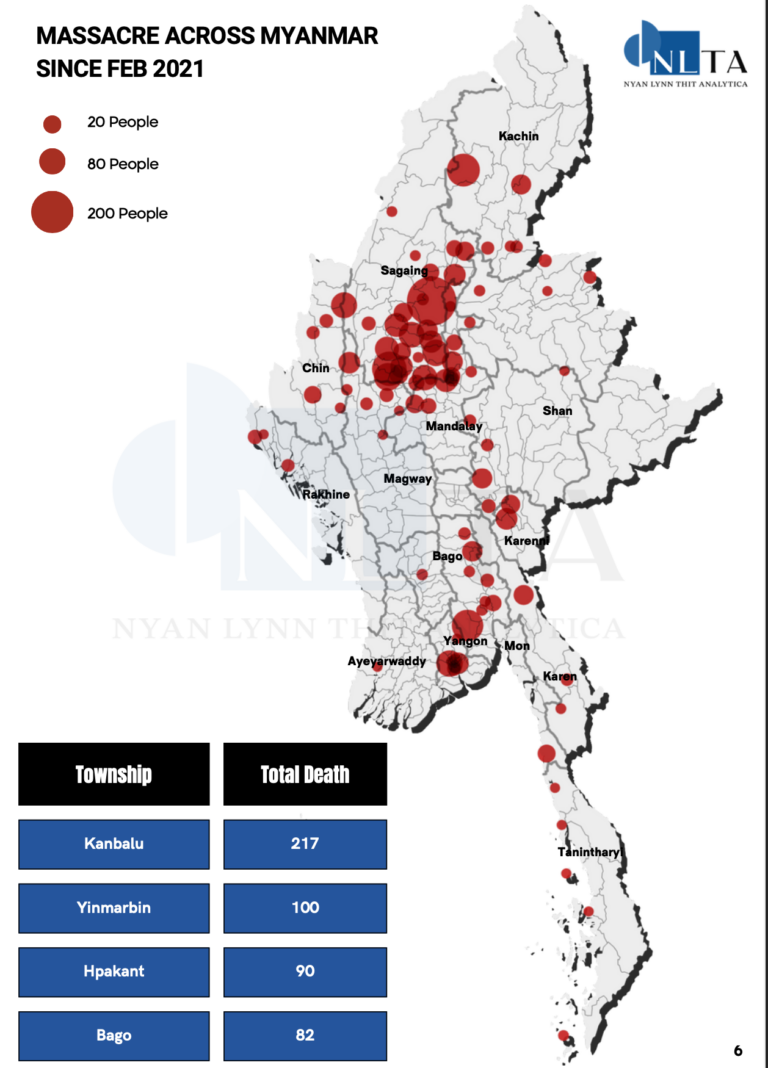

Of the airstrikes conducted by the Tatmadaw, Sagaing is the most affected region, to date.

In the Pazigyi Massacre, the deadliest attack of 2023, hundreds of people lost their lives. On the morning of April 11, the Tatmadaw used a Yak-130 fighter jet to attack a large crowd of people who had gathered for the opening of the local office of an opposition movement. Later that afternoon, Mi-35 military helicopters returned to target the first aid team conducting rescue operations. A total of 174 people were found dead. Among them were 38 children and 25 pregnant women, all casualties of three separate attacks by the Myanmar air force in a single day on Pazigyi village.

On June 27, the military conducted a raid using fighter jets on the village of Nyaung Kone, in Pale Township, Sagaing Region. At least 10 locals died because of the bombing.Ten minutes after dropping the first two bombs, they dropped another, and sprayed the village with machine gun fire. One monk, seven men and three women were found dead. The ages of those who lost their lives were between 22 and 70. An institution in the monastery was destroyed and 13 houses were wrecked in the bombing. Nyaung Kone is a village with over 200 residences and is 12km away from Pale. Many fled the village after what happened.

On January 7, 2024 Tatmadaw fighter jets carried out an airstrike on Kanan village, off Tamu Township in Sagaing. Early in the morning a bomber identified as an A-5 dropped five bombs near the school and church. 16 people died, including four children under the age of three.

Cover Image by Diego Rivera, “The Perpetual Renewal of the Revolutionary Struggle”, 1927, Mexico

Map & Graphs by Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica