Burmese protesters live streamed the protest on February 1, 2023 in front of the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok.

© Nicha Wachpanich / Visual Rebellion

“If I don’t post, am I part of the revolution?”

—> Read this article in Burmese

In Myanmar, a country that has been long wrestling with political instability, Facebook can be regarded as synonymous with the internet and freedom of expression. After the 2011 general elections – the first in over 20 years – Facebook was further established as the main public space for people to participate in politics, especially for the Myanmar people who were new to the use of mobile internet and social media platforms. Today, there are more than 19 million Facebook users in Burma in May 2023, accounting for one-third of the population. Many of these users have continued to use the platform in support of the anti-coup movement, following the Myanmar military’s seizure of power in February 2021. And amidst the lively campaigns and other posts in resistance to the coup, pro-democracy netizens are encountering another type of anxiety, asking themselves, “Am I posting enough about the resistance online? If I’m not posting enough, will I be considered as pro-military or cold-hearted?”.

For the over 1.3 million Myanmar people who have since become refugees and asylum seekers, social media and other digital spaces are their only way to stay updated and take part in politics, changing profile pictures to show condolence for the tragic airstrikes, sharing campaigns, and even criticizing other Burmese netizens who appear to be pro-military.

Researcher Chu May Paing, a Bamar anthropologist currently based in the United States, has been studying since 2021 this new wave of social media activism in Myanmar.

Her research on Burmese netizens’ use of social media focuses on how they use the languages in social media posts, messages and visual representations to share their reactions and feelings about certain major social events in Myanmar. She argues that people’s interactions with social media are more than a tool of communication, and that social media in and of itself has become the way of life for Myanmar people in dealing with not only politics but also their everyday activities, ranging from selling clothes via Facebook lives to attending online protest events via widely used conferencing platforms.

Visual Rebellion talked to Chu May Paing in March 2023 to understand further the motivations and significance of this phenomenon in spite of the digital safety and security risks. The interview below has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Visual Rebellion (VR): What is your research about?

Chu May Paing: I’m looking at social media activism specifically among the diaspora who have fled Burma after the recent coup. As an anthropologist, I am not studying how people use social media or what are the percentages of the country’s population that have access to these platforms. My interest is more about how people use social media platforms to remain engaged with homeland politics.

I was born and raised in Yangon and moved to the United States in 2012. As I also belong to this diaspora community, I am also participating in these digital spaces, so my methodology is what anthropologists call ethnography – collecting data through interviews and participants’ observations and also a description from my own positionality and participation in these digital spaces.

VR: Why does social media have such a significant role in Myanmar politics?

Paing: After Burma’s liberalization period, when Aung San Suu Kyi and the [National League of Democracy] government was in charge, the internet became more readily accessible to the general public.

So if we look back to the political history of Burma, in my opinion, the debate is always about who has the most legitimacy to hold power. Even though they are in charge or whatever the names that they give to themselves, they still have to practice some kind of actions to prove that they are legitimizing their power.

This characteristic not only exists in Burma, and is representative of the ways in which power works in Southeast Asian cultures. Imagine a game of volleyball. You got like a ball of power, and anybody could grab that volleyball from your hand. And then whoever has the volleyball in hand holds the power, right? So it’s always this playing field, and how are you going to grab the ball from this person?

Before the time of social media, those who want to prove that they are legitimate to the position might use supernatural claims or astrology to show to the audience that they are worthy of this volleyball – this power that you have. But in the present days, taking control of social media is like taking control of this ball of power. And unlike supranatural media, social media seems to offer a level playing field for both sides.

The digital spaces have become an arena for the military to justify why they should be in charge. But in the meantime, people also treat social media as a space where they can make jokes and showcase their anti-military standpoints. It allows them to become political subjects and to express their opinions even if only among their list of friends. Before, these conversations only happened in the tea shops.

So the central question of my project is, how can we understand this new form of technology in the context of a very culturally specific understanding of power? Social media are not separated from all other social and cultural values, but they are all deeply intertwined to the rest of society.

VR: What have you found interesting about Myanmar’s social media activism?

Paing: My focus is on anti-military movement interactions on social media. People are very playful with the limitations on these digital spaces. In 2018, Facebook put into place community regulations specifically after numerous instances of hate speech against the Rohingya. But identifying hate speech is very culturally specific and the automated machine faces difficulties to catch up with the playfulness displayed by people.

One example is that Facebook tried to regulate accounts or posts that contains the word အသတ်ခံရ (pronunciation: aathetkainya) which means « to be killed ». So people began to post about deaths in ´Burglish’: အthetခံရ which it pronounced similarly but won’t be identified as such by the machine.

Facebook is a home base for Burmese users. According to data from February 2022, there were 20,790,000 Facebook users in Myanmar which accounted for 36.8% of the entire population. There are also users on other platforms, especially Twitter. Right after the coup, there was a rush of social media users moving to Twitter to communicate to the international audiences about what’s happening in Myanmar. But after two years have passed, the situation hasn’t improved so people are not really active on Twitter anymore, compared to Facebook.

VR: Which risks or challenges does social media activism carry?

Paing: Many users were arrested after posting anti-military views on Facebook. Pro-military Telegram channels spread screenshots of those posts and publish personal information about their authors. People have actually been detained just from changing their profile pictures to black [as a sign of mourning for victims of airstrikes]. So these posts became very materialized in the actual real political arena.

As much as it is risky to show anti-military standpoints on social media, one feels an urge to post about it. Although people tend to think anti-coup activists are all happily unified, there is a tension within.

Some activists claim that social media activism doesn’t count as real activism because of not going out on the streets any more. We used to have a lot of street protests before in Myanmar. But the military now is in control of the cities, so people don’t do that anymore. Instead, some joined the armed resistance movements on the borderlands. So are you really fighting if you’re not taking up arms or are you really going into the jungle if you don’t take a picture and then post it on social media?

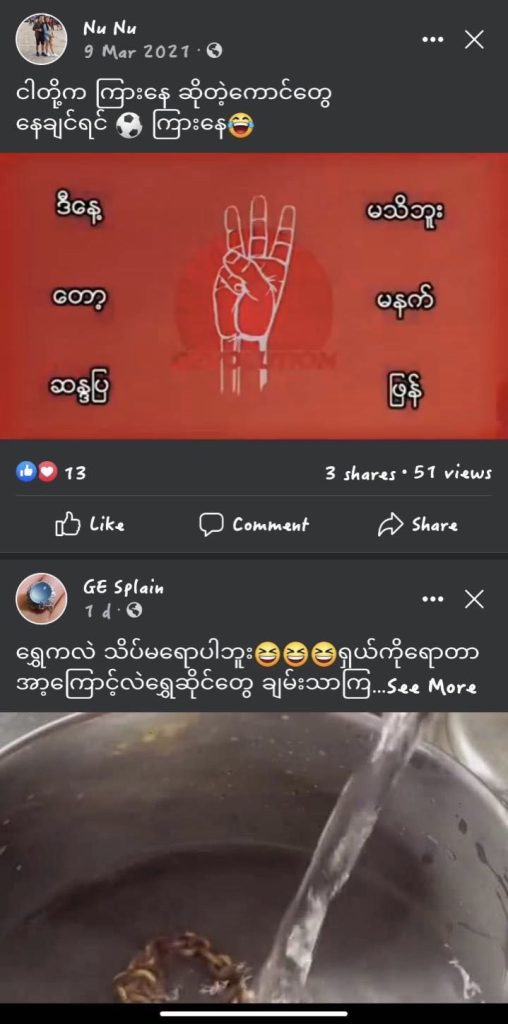

At first, people were more concerned over leaving digital footprints, but as many months have passed, this kind of social interpretation has also evolved and changed. Now some people are saying that if one locks their Facebook profile picture and the others can not see it anymore, it is because one is scared to show their own stance. If you are truly anti-military, you would not be scared to be viewed, they say.

VR: Is it because people in exile only have social media as a tool to express their concerns and activism?

Paing: That is also why I am interested in looking into this concept of shame and guilt. As one carries a lot of guilt and shame, it also leads to shaming other people back. Shaming is also to me a very specific Southeast Asian cultural feeling. This collective feeling can be nurtured among the family that one is growing up into. Feeling embarrassed alone is not enough, everybody who is connected to you has to feel ashamed too. So every action that you do, you affect your social cycle. So at a nation state level, every citizen must then behave correctly. So that your whole country is not embarrassed, right?

That also applies to those in the diasporas, especially the first generation migrants and those in exile. When you are far away from home or left home for various reasons, one of the only ways you could remain in solidarity with those inside the country is through actions on social media. This use of social media to signal one’s national belonging even when in the diaspora is not new, not just the Myanmar one. Social media makes it more affordable and easier to practice what anthropologist Benedict Anderson terms “long-distance nationalism” to refer to the diasporic movements and actions towards homeland national politics. If you don’t post or even reshare anything about Myanmar, do you still belong to Myanmar? If you don’t post a picture of yourself wearing a blue shirt holding up three fingers as instructed by some digital strike campaigns, attend Zoom protests, or “click to donate” [monetary support] for Myanmar, do you still care about Myanmar?

This whole debate just happened recently. In April 2023 before the Thingyan celebrations, a huge bombing by the military in Pa Zi Gyi village, Sagaing region, killed dozens of civilians. People changed the profile picture to black in condolences for the people who got killed. Social media creates bubbles that polarize different opinions and there is no nuance or shades of differences. It has become either changing your profile or not changing it. If you don’t change it? This means you don’t care about the people who died or you have gone cold-hearted, because it would be such a small action to undertake.

So here is when you look at social media, they are not just the tools for people to use but they have become very much embedded in our lives.

VR: Do you think people should use social media or not?

Paing: I couldn’t recommend to anyone whether they should use or stop using social media. As an anthropologist, it is not my place to offer a solution, but I would say there is so much more to study about it as a cultural specific form. Different platforms have different people interacting on it and with Myanmar being composed of so many different ethnic groups, all of them have their own Facebook channels and languages. I’d say that Bamar social media doesn’t play out the same way Kachin or Kanyaw social media just like Thai social media wouldn’t work exactly the same as Indian social media.

We cannot afford to say oh, it’s just social media, just a medium of communication or social networking, even a toxic one at that, but it’s become the subject of everyday social, cultural, and political interaction in and of itself a whole social arena where for Myanmar people, a day could not go by without checking, posting, or discussing about what’s happening on social media when it comes to our everyday sociopolitical life.

In order to do social media activism, there is a challenge of surveillance capitalism. You could even be arrested from what you are saying on Facebook and the screenshots of the post, But, we cannot leave. If we leave Facebook, how we’re gonna keep in touch with our family and how we’re gonna keep an eye on the country they are living in?

This story was first published on Engage Media and was written by Nicha Wachpanich of Visual Rebellion, a collective for Myanmar journalists, photographers, filmmakers, and artists to publish their productions following the 2021 military coup.

A project supported by the ‘Staying Resilient Amidst Multiple Crises in Southeast Asia initiative’ of SEA Junction in partnership with CMB Foundation.