Military juntas in Myanmar systematically destroyed historical landmarks, driven by their own political and economic interests. The Students’ Union Building fell victim to the military junta’s political tactics, and its explosion was intended to intimidate both students and the general public. The grounds of Jubilee Hall, initially demolished for the junta’s institutional interests, were later sold out for the economic gain of cronies and generals. Both places hold huge national significance, representing the spirit of anti-colonial, anti-fascist, and anti-dictatorship struggle. This collective memory should be preserved in the face of the erasure of history undertaken by the successive military regimes.

By Pai Cheimt Khaung and Haymarn Soe Nyunt

I) Students Union Building

In the early hours of July 8th, 1962, students in the University of Yangon awoke to a thunderous explosion that ripped through the whole campus. The iconic Students Union Building has been demolished, and an indelible piece of their shared heritage was forever lost.

Echoes of the Past // Military Coup and Rules

It all began with a military coup by General Ne Win on March 2nd, 1962. Two days later, All Burma Federation of Students’ Union (ABFSU), University of Yangon Students’ Union (UYSU), and Yangon District Students’ Union (YDSU) took a stand against the coup, issuing a joint statement of condemnation. They were the first to raise their voices against the military’s usurpation of power.

In response, Ne Win’s junta swiftly abolished the Yangon University Act and dissolved the Yangon University Council, which included respected professors and student representatives. They replaced it with a new University Council, comprised solely with generals and a handpicked rector, devoid of any independent voices from within the academic community.

The military imposed stringent regulations on the campus hostels, transforming them into virtual prisons. These rules restricted students’ movements after dusk, confining them rigidly to their rooms, and imposed arbitrary limitations on eating hours at the dining room.

Adding insult to injury, the junta invalidated the matriculation exam results, alleging that the questions had been leaked. However, the students argued that the responsibility for any leakage lay not with them but with the authorities and the flawed system itself. Punishing the students by canceling their exam results instead of addressing systemic issues and corruption was unjust.

On July 3rd, students initiated protests within the confines of the Yangon University Campus, ignited by the enactment of prison-like hostel regulations and the unjust cancellation of exam results.

Day of the Massacre

On July 7th, the police arrested several student leaders, including ABFSU president Ko Thet, UYSU president Ko Ba Swe Lay, and YDSU general secretary Ko Nyan Win. This act further exacerbated tensions and students’ outcry. The police attempted to seize control of the Students Union building, resorting to anti-riot batons and tear gas to disperse the students who vehemently protested the arbitrary arrests of their leaders.

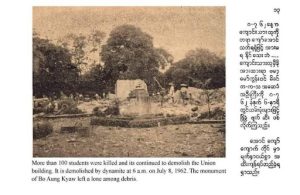

The soldiers took position outside the campus, armed with newly-produced G3 guns, and opened fire on the students. The ensuing gunfire claimed over a hundred students’ lives that day. As dusk fell, in the darkness, soldiers silently carried away the bodies of these fallen students, concealing the true extent of the massacre. The following morning, the military reduced the Students Union Building to rubble using explosives.

[ Read our feature on Seven July remembrance day in Yangon in 2022 ]

Anti-Colonial Bastion

The University of Yangon Students’ Union Building is historically significant for the nation, as it served as the epicentre of the anti-colonial independence movement from the 1930’s. From its very roof, independent leaders emerged, and resistance activities aimed at dismantling colonial rule were born.

Throughout history, students in Burma stood up against injustice, whether it came from colonial authorities, civilian governments, or military dictators. This indomitable spirit and unwavering commitment may have posed a threat to the newly formed junta, prompting their decision to repress the students’ union from the early days of their rise to power.

The infamous event is widely known as “7 July,” and ignited an ongoing struggle between student unions and military dictatorship. Since then, the junta has employed various tactics to subdue student unions at every turn. The demolition of the Students’ Union Building remains as a stark symbol of the junta’s relentless oppression, revealing their true face of violence and disregard for the general public.

Students Will Not Dance on the Blood of Fallen Heroes

In 2015, the National League for Democracy (NLD) Party won a landslide victory in the election held under the 2008 Constitution, which guaranteed military control over essential offices. During their governance, the NLD proposed the reconstruction of the Students’ Union Building, and included the cost in the parliamentary budget.

Recognising the significance of this endeavour, ABFSU organised a conference in 2017, inviting student leaders from the 1950s to the present day. The purpose of the conference was to ensure that the rebuilding was not a decision made by a single group as the matter concerned all generations. During the conference, some student leaders emphasised the importance of obtaining official recognition for student unions. Student unions were still not legal, making it crucial to address this issue before rebuilding the iconic structure.

They asked, “What purpose does the Students’ Union Building serve if there is no student union to occupy it?”

A group proposed that the area should be transformed into a symbolic and educational place. Drawing inspiration from the preservation of sites like Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the suggestion was to use the space to showcase the history of the Students’ Union Building and its demolition. Such a memorial would serve as a testament to the brutality of the military dictatorship and the courageous sacrifices made by countless students in the struggle against the regime. The new Students’ Union Building could then be constructed behind this memorial site.

Another crucial point brought up was the fact that the government, operating under the 2008 Constitution, was not a fully civilian government. Power-sharing with military generals in essential sectors, including Defence and Home affairs, undermined the pursuit of justice for the victims of the 7 July incident, which ultimately led to the demolition of the Students’ Union Building. The NLD government prioritised reconciliation with the military dictators and sought to downplay this dark chapter in history.

Students who commemorated the events of 7 July were even subjected to arrests so leaders from different generations argued that the reconstruction of the Students’ Union Building on the blood of those who fell in 1962 would be an insult in itself. They demanded that the government compile a comprehensive list of the students who lost their lives on this fateful day, officially recognise their sacrifices, and acknowledge the brutal nature of the junta’s actions before proceeding with the rebuilding.

A last suggestion emerged during the conference, that the government’s budget, which had been part of the system responsible for the killing of students on 7 July and the demolition of the Students’ Union Building, should not be utilised for the reconstruction. Instead, it was proposed that crowdfunding from the public be employed, and that the process of rebuilding the Students’ Union Building be led solely by student union leaders. After all, this was a building that belonged to the students themselves.

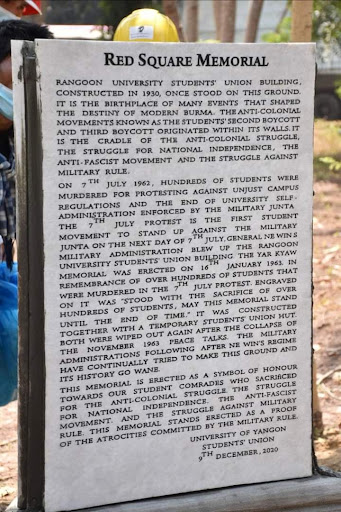

Echoes of Resistance // Reclaiming the Students Union Building’s Legacy

In 2020, the University of Yangon Students Union planned to establish a stone inscription at the site formerly occupied by the Students’ Union Building, now known as “Red Square.” This inscription would detail the history of the military dictatorship’s brutality and the sacrifices made by students in their anti-colonial, anti-fascist, and anti-dictatorship struggles. The NLD government and university authorities halted these efforts, citing COVID-related restrictions that allegedly prevented the hiring of construction workers specifically for the inscription. Curiously, other university buildings were being repaired with construction workers during the same period.

On February 1st 2021, a junta led by General Min Aung Hlaing staged a coup, triggering widespread demonstrations against this illegitimate seizure of power. On February 25th, University of Yangon Students’ Union organised a student meeting at Red Square. The outcome of that meeting was a resounding rejection of military dictatorship, a call for federal democracy, the abolition of the 2008 constitution, and unequivocal support for the Civil disobedience movement.

The stone inscription, previously hindered by the NLD government and university authorities, was finally unveiled and planted at Red Square. Despite the presence of police and soldiers surrounding the campus, the students conducting the meeting remained unharmed. Erecting the stone inscription amidst the anti-coup mass demonstrations was a powerful moment. No matter how much the dictators sought to destroy and repress student unions, the spirit of campus activism would never waver, persisting in the face of daunting adversity.

II) Jubilee Hall

Another significant loss was the Jubilee Hall. Located on Shwedagon Pagoda Road, it was completed in 1897 to mark the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria, commemorating the 60th anniversary of her reign. The building had replaced a complex of assembly rooms used by the colonial administrative apparatus, first constructed in 1854.

Later, it was appropriated by Burma’s independence movement and served as the venue for crucial conferences and events, such as the very first conference of ABFSU and the meetings of the General Council of Burmese Associations (GCBA) that determined the stance on the British colonial dyarchy system and National Day every January 4th.

In 1947, Jubilee Hall also hosted the state funeral of the nine martyrs gunned down on July 19th, including the revered General Aung San, as well as the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) conference that preceded the formation of the constituent assembly, shaping the foundation of the country’s first independent Constitution.

Despite its initial construction catering to colonial interests, Jubilee Hall had become a symbol of the anti-colonial struggle and the quest for independence. Due to its historical significance, the hall was rightfully transformed into a national museum and national library in 1952 under the AFPFL government.

Generals Dance on the Blood of Martyrs

During U Ne Win’s military regime in 1985, which was disguised as a socialist regime, Jubilee Hall was demolished to make room for the construction of a Defence Services Museum (DSM).

In 2013, under Thein Sein’ military regime, the DSM itself was demolished. The land where the historically significant Jubilee Hall once stood was then leased to the Y Complex, primarily owned by Japanese investors. According to reports from Justice for Myanmar, the Y Complex is a US$320 million development project in Yangon city centre that encompasses Okura Prestige hotel, shops, and offices.

Significantly, the rental fees generated from this lease arrangement do not contribute to the public budget, but rather flow directly into the pockets of military generals through the Quartermaster General office. This office, responsible for procuring weapons, has been increasingly implicated in the use of such weaponry to perpetrate violence against civilians. Justice for Myanmar’s investigation further revealed that the lease agreement stipulates the direct transfer of land rent funds to the Quartermaster General’s office via a proxy company.

The demolition of Jubilee Hall and the subsequent commercialisation of its land underscore the government’s disregard for historical preservation, the welfare of its citizens, and reveal the disconcerting reality of financial exploitation of the country’s entire resources by the Myanmar generals.

The Impact of Blood Money on the Streets

This diversion of funds, which should rightfully serve the public interest, towards the military’s weapon purchases only exacerbates the suffering and loss of life inflicted on the civilian population. In the wake of the February 2021 coup, the military’s violent actions against its own people have peaked, making this misuse of funds all the more abject.

The actions of the military junta and their proxies serve as a harsh reminder of the urgent need for justice, accountability, and the preservation of Myanmar’s historical treasures. They not only erase important chapters of the country’s history, but they also feed a vicious cycle of violence and oppression.

WHAT REMAINS OF LOST LANDMARKS

The act of destroying Myanmar’s Students’ Union Building and Jubilee Hall carried out by the military regime signifies more than mere physical destruction. These structures held great historical value as symbols of the nation’s endeavours for independence, anti-colonialism, and democracy. The demolition also endangered the cultural legacy and shared recollections linked to these places. Despite their demise, the significance of these lost landmarks endures.

- Symbolising Resistance and Struggle

The Students’ Union Building stood as a symbol of resistance and a monument to Myanmar’s students’ courageous spirit. It was a meeting point where anti-colonial and anti-dictatorship groups arose, and many leaders emerged to fight for the country’s freedom. The military junta deliberately destroyed it in order to silence student protests and scare the broader crowd of civilians. The legacy of the building and the sacrifices made by those who battled for justice and democracy, however, continue to inspire present and future generations.

Similarly, Jubilee Hall symbolised the struggle for independence and the establishment of a sovereign nation. It witnessed significant historical events and conferences that shaped Myanmar’s history. The renovation of the hall into a national museum and library increased its value as a repository of information and a symbol of the nation’s identity.

- Inspiring Movements for Democracy and Justice

A new spirit of resistance and tenacity has been sparked among the people of Myanmar as a result of the destruction of the Students’ Union Building and Jubilee Hall. The struggles for justice, democracy, and an end to military oppression were spurred by these terrorist acts.

The memories connected to the Students’ Union Building and the selfless deeds performed by students on “7 July” continue to serve as an example. Inspiring advocacy and mobilisation against the military regime is the students’ courageousness in the face of terrible repression. It serves as a reminder that the pursuit of justice and democracy requires steadfast dedication, particularly in a time of hardship.

The demolition of Jubilee Hall has embedded a sense of injustice in the population. The commercialisation of the land and the transfer of revenues to the military expose the regime’s authoritarian nature even more. This awareness has galvanised groups calling for responsibility, transparency, and an end to financial exploitation.

- Unlocking the Future: Toppling the Junta to Safeguard Myanmar’s Historical Identity

Myanmar’s military regime’s destruction of those buildings is a catastrophic loss for the country. These landmarks represented Myanmar’s struggles and aspirations. Their destruction was meant to stifle people’s voices and erase the cultural memory associated with these sites. But these vanished landmarks continue to inspire movements for justice, preserve historical identity, and remind the Myanmar people of their indestructible collective spirit.

To preserve Myanmar’s history and heritage for future generations, immediate action is needed. This includes raising awareness about the value of these sites, advocating for change, and supporting projects to recover and restore them. Unethical practices must be exposed and rectified, while penalties on the Myanmar junta should be demanded. It is crucial to ensure that proceeds from historical sites benefit the people instead of supporting the junta. International organisations and concerned individuals have the power to raise awareness, assist local activists and organisations, and exert pressure on Myanmar for significant change and restitution.

Achieving these goals is highly unlikely under the current military dictatorship, which prioritises erasing factual history for its own benefit and myth. Only through the establishment of a free and inclusive government and a democratic society can the necessary measures be taken to preserve the historical sites where people thought together at another path for the country.

References

“Will the Centenary of Myanmar’s Yangon University Lead to Re-Establishing the University Student Union Building?

A discussion with YUSU chairman Ko Nyi Nyi Zaw and U Ko Ko Gyi, one of the leaders of the ABSFU in 1988 and chairman of the People’s Party”, The Irrawaddy, 2020

“Jubilee Hall—From Colonial Social Hub to Hotbed of Myanmar Independence Activity”, The Irrawaddy, 2020

==> Watch the ABFSU Conference with leaders from all generations on the reconstruction of the Students’ Union Building (2017) :

Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4 / Part 5 / Part 6 / Part 7 / Part 8 / Part 9 / Part 10 / Part 11

“History of the Burmese students movement”, Aung Tun, 2007

“Burma in the Darkness”, Win Tint Tun, 2007