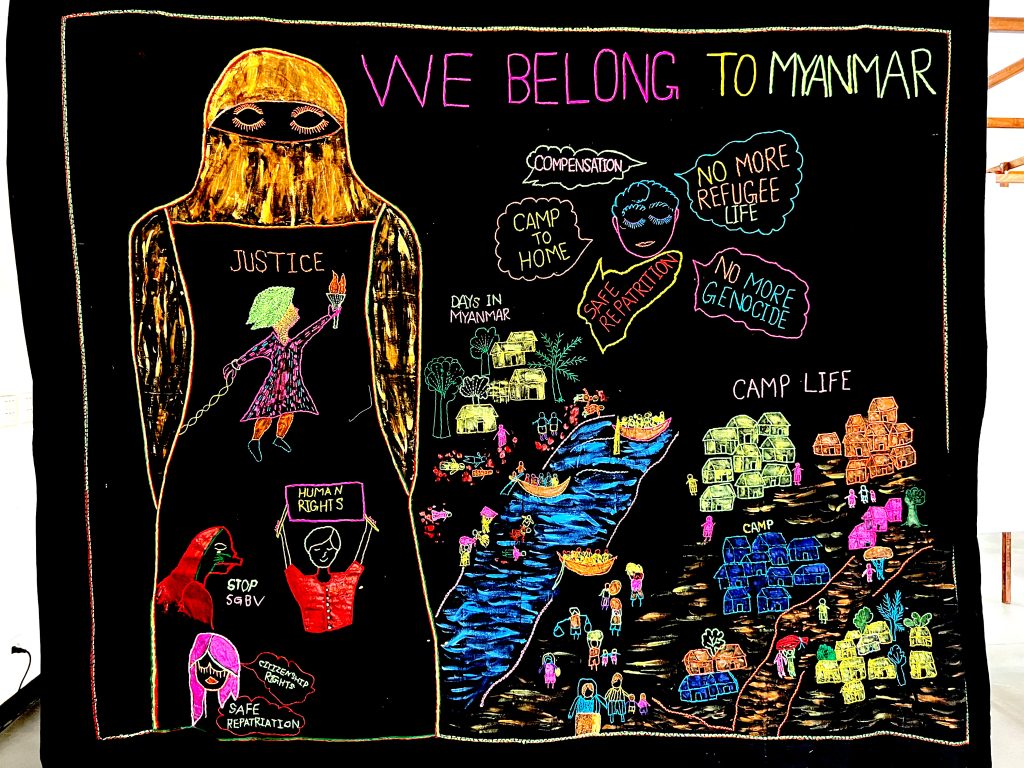

© A quilt made by Rohingya women living in refugee camps in Bangladesh / AJAR

/ ROHINGYA REMEMBRANCE DAY /

Interview with Razia Sultana, lawyer, educator and human rights activist

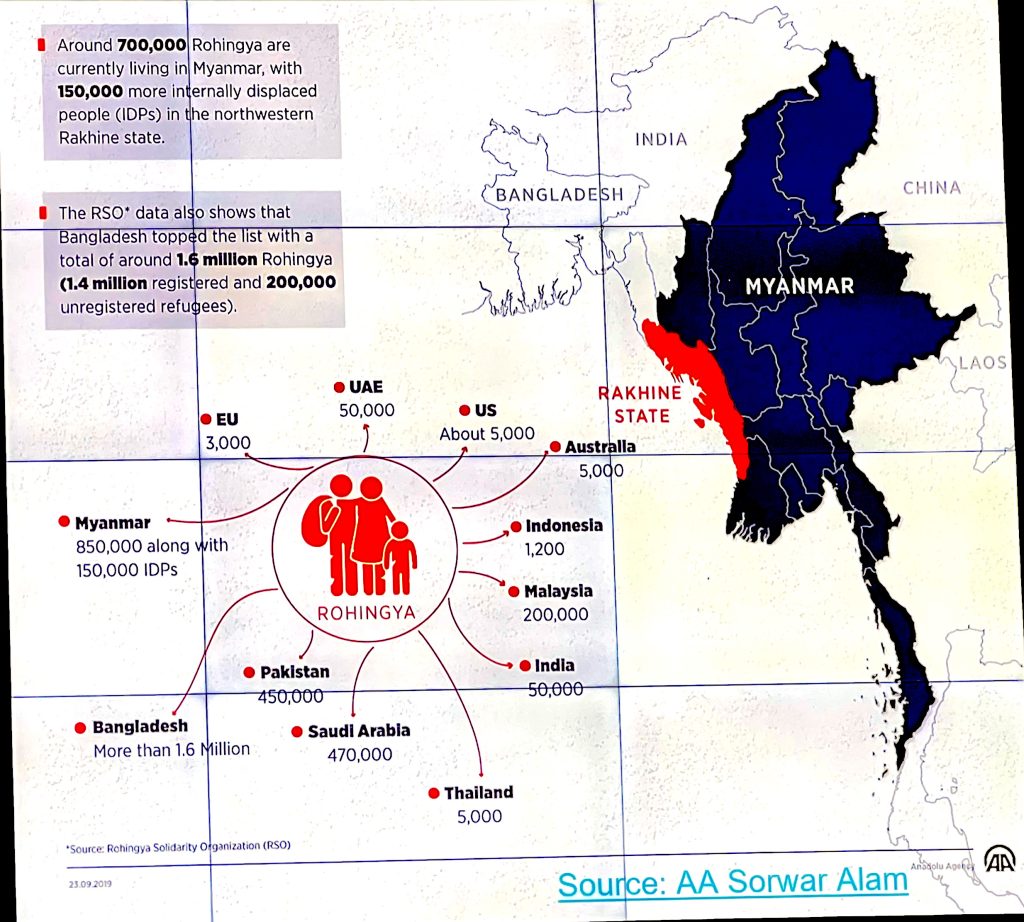

Rohingya people belong to an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, who mostly believe in Islam. They lived mainly in Rakhine state, Myanmar, despite having been stripped from their citizenship rights since 1982.

Rohingya people belong to an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, who mostly believe in Islam. They lived mainly in Rakhine state, Myanmar, despite having been stripped from their citizenship rights since 1982.

From October 2016 and then August 25th, 2017 onwards, Buddhist Rakhine nationalists and later the Burmese military launched a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing and forced deportation, which has sent a million Rohingya people running for their lives across the Naf River to seek refuge in Bangladesh.

On the edge of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, the Kutupalong-Balu Khali expansion site is the world’s largest refugee camp and is inhabited mostly by Rohingya people. A few thousands Rohingya people remain trapped in camps in Rakhine State where they bore the full impact of Cyclone Mocha on May 14th, 2023.

For Remembrance Day on August 25th, 2023, Visual Rebellion spoke to Razia Sultana. She is a recipient of the International Women of Courage Award, interpreter and researcher at Rohingya media organization Kaladan Press, and founder of the Rights for Women Welfare Society (RWWS), which supports Rohingya women survivors of large-scale abuses by armed groups.

Could you introduce yourself and your work?

My parents migrated legally from Eastern Pakistan – present-day Bangladesh – in the 1960’s. I was raised in Bangladesh and studied teaching and law.

My advocacy journey began in my student days, and I have remained engaged with community-based initiatives since then.

I recognize the decades-long atrocities faced by Rohingya, leading them to seek refuge in Bangladesh since the end of the 1970’s. While many Rohingya returned to Myanmar in the following decade, the situation changed again in the 90s, when they couldn’t return and remained stranded in the neighboring country because of a new large-scale “clearance operation”.

I have been interpreting for international news and humanitarian agencies since 2012. It was especially challenging before the 2017 mass exodus from Myanmar, as Rohingya refugee registered camps were off-limits at the time.

My involvement with Rohingya news agency Kaladan Press started in 2016 when I assisted foreign reporters and researchers during the crisis. Interacting with female survivors and witnessing their suffering motivated me to gather more information.

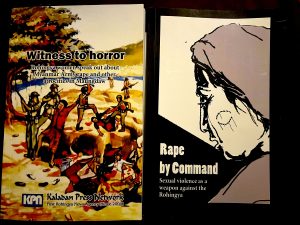

We published “Witness to Horror”, a report I presented at the People’s Tribunal High Hybrid Court in Malaysia in 2017. This report exposed the intentions of the Myanmar government and military forces in the Rohingya genocide. I also addressed the UN Security Council with key findings and insights.

“Solidarity and support is not only my target, but a mechanism to bring justice by exposing perpetrators and their accomplices”.

Razia Sultana Tweet

➽ Read the Special Issue on the Rohingya crisis by the Independant Journal of Burma Studies (December 2021) and especially the chapter “Militarization in Northern Rakhine State: How,Who and Why” by Wai Moe.

Could you share updates on the legal and humanitarian situation for the Rohingya community, both in Myanmar and abroad?

The situation for the Rohingya community remains dire, both in Rakhine state and in their places of exile, such as Bangladesh and other countries.

The Rohingya, who have faced forced displacement and genocide, continue to be labeled stateless and homeless by UN experts and human rights advocates. The Rohingya’s longing for recognition and rights in their homeland remains unfulfilled, as they’ve been systematically denied citizenship, education, political representation, and healthcare in Myanmar for decades. This lack of social and legal status renders them practically invisible, despite sharing land with other many ethnic groups.

While repatriation from the refugee camps in Bangladesh to Myanmar is often proposed as a solution, it has not yet begun, and the situation has worsened with the military coup in February 2021. The military junta shows no intention of accepting the Rohingya who fled their homes and crossed the border to save their lives. Past instances of violence, including the 2017 genocide, continue to cast a shadow on their prospects for a safe return.

In the refugee camps in Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees face overcrowding, reduced aid, limited movement, and increased domestic violence due to the pandemic’s impact.

Bangladesh’s relocation plan of Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char island since December 2020 is met with fears of more flooding, isolation, and insecurity.

➽ Read the report “An island jail in the middle of the sea” by Human Rights Watch.

Efforts to achieve citizenship and recognition as an ethnic group within Myanmar remain critical for the Rohingya. They seek justice for the atrocities of 2017 and a return to their ancestral lands, rather than planned detention camps.

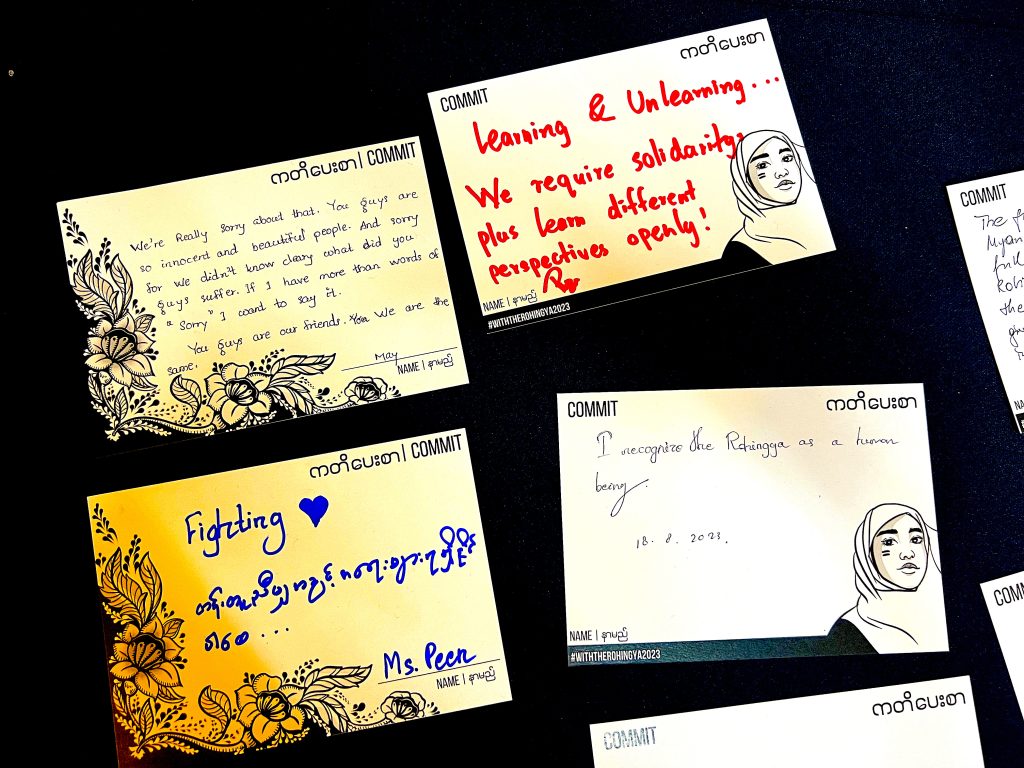

The international community’s response to the Rohingya crisis has fallen short and need to step up with meaningful action. Diplomatic and economic sanctions are necessary, along with investments and aid contingent on ending ongoing atrocities and enabling Rohingya’s safe return and recognition as citizens in Myanmar.

Amira, a 35 yo tailor, with her six-months baby

"I can earn 100 to 200 BDT (0,90-1,80 USD) a day to buy clothes and snacks for my children. But since last month, I don't receive enough nutritious food for them since the World Food Program reduced the amount of ration allowance from 10 to 8 USD per person and per month" © Shahida Win / Rohingyatographer

When talking with women that have suffered such atrocities, what are the ways that you approach these conversations and how did you manage to preserve their stories without triggering a negative feeling in them about retelling it?

When conducting my interviews, regardless of gender, I know not to just directly ask “What happened to you?”. I never want it to be simply an interview, but rather a conversation. I always begin by introducing myself, and telling them that they do not have to talk to me if they do not feel comfortable. I always make sure to prioritize the victims’ and witnesses’ comfort, ensuring that the interviews are conducted in a safe environment and that their medical and emotional needs are taken care of through NGOs and international programs.

If they decide to go through with the interview I guarantee that their identity will be protected, as we have specific rules to follow under international witness testimony laws. We are not allowed to disclose witnesses’ identities, and can only share their testimonies with reputable international organizations dedicated to justice and protection.

On a more personal note, at times it can be difficult to refrain from my own emotions when involved in this type of research such as the one for Rape by Command, another report published by Kaladan Press. I described my own trauma in my first report Witness to Horror and had to receive psychiatric treatment. I was a very calm, cool, and collected person. After these incidents occurred, I became aggressive, yelled at simple issues and my attempts to control my anger were futile at times. I now feel heightened emotions around issues of injustice, particularly those involving women. This emotional transformation, while challenging, underscores the gravity of the work I currently partake in.

What was the reasoning behind the separation of men from women and children amidst these atrocities? [TW: Sexual Violence]

Quite simply, when supreme powers want to divide a nation, they attack women and children to enforce their governance. Sexual abuse and rape are widely-used weapons of war by those who want to instil fear into civilians’ minds. Especially after the 2016-2017 Rohingya mass exodus, the separation of Women, Children, and Men is to ensure there are no defensive measures taken when enforcing rape.

Rape has been used as an integral element of modern-day apartheid. Rape has been a central component of the genocidal campaign waged by Myanmar’s military and security forces against the Rohingya ethnic minority, in which Muslim women and girls – and also men and boys — have suffered unspeakable sexual violence.

Several agencies such as the United Nations-mandated Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) found various evidences of sexual violence across Myanmar. Over 80% of the cases were perpetrated collectively, such as 30-40 women and girls gang-raped together in a school among other incidents.

Those issues are particularly delicate and profoundly important, and societies have to continuously work to protect women and children from any kind of unforeseen violence or assaults. The disturbing developments that had been occurring for decades came to a head in the events of 2017. The Rohingya population in Myanmar had not yet reached the point of deciding to leave their country, despite the difficulties they had faced over the years. But the situation worsened and violence began to specifically target women and children. In order to protect their families from this dire situation, they were forced to make the difficult decision to leave their ancestral lands and seek safety in other parts of the country or abroad.

Do women affected by those traumatic abuses have access to any resources to help them cope with the aftermath?

Since 2018, I have been running a psychological resilience and healing centre for Rohingya refugee women, with partner NGO Asia Dignity Initiative (ADI), which is funded by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA).

The project encompasses a range of strategies:

– The establishment of peer groups among families and neighbors to expand social networks within Rohingya communities.

– The provision of a dedicated safe space for women’s mental well-being and protection.

This initiative also endeavors to empower both Rohingya and Bangladeshi women via inclusive activities designed to address pressing issues such as premature marriages, trafficking, and sexual violence against women and children.

The Female Psychosocial Support Groups are at the heart of this project and serve as the primary agents of change. They undergo four distinct qualification courses: Practitioner, Assistant, Master, and Trainer. Each course is structured with a curriculum that advances from beginner to advanced levels, with a strong focus on supervision and hands-on experience.

Graduates of the Practitioner course organize self-help groups to apply the learned programs in their daily lives and to offer support within the community. The Assistant course combines intermediate psychosocial support training with practical exposure to the Women’s Healing Center operations. Master course trainees develop specialized skills to address specific symptoms and are empowered to autonomously manage the Women’s Healing Center. The final Trainer course equips participants to oversee branches of the Women’s Healing Center and become proficient in training others as practitioners and assistants. This comprehensive approach forms the basis of the ‘Female Psychosocial Support Group Training Model,’ which aims to expand the network of psychosocial experts within the community.

Our Women’s Healing Center serves as a crucial hub for Rohingya and local community women and comprises different healing zones – body, mind, soul, integral, and spiritual – and livelihood zones – chicken coop, kitchen, daycare, and gardening. The center also includes a dedicated training room for workshops and community leaders meetings.

Does the community and especially women have access to education or employment in Myanmar or abroad?

Education is the pillar of any nation. Education is the only way out to save our people in the long run. In Myanmar, there is no intention to give education to Rohingya youth. In Bangladesh, I have seen the shutdowns of hundreds of self-running schools within the camps. Without education, frustration in the community only grows. It is essential that basic formal education is implemented in the Rohingya community with proper programs. And it’s even more important that women and girls are able to benefit from these opportunities equally. The vast majority of adolescents aged 15 and over lack access to education, and this is especially acute among girls.

Illiteracy has a harsh impact on women as it makes them more vulnerable. A community with high levels of illiteracy is also prone to bias no matter their religious beliefs, political ideologies, or social status. These lack of opportunities have led to limited recognition of one’s own responsibility, leading people astray. Educational awareness programs will have to be the gateway to make Rohingya women and men understand what is right and wrong.

Has there been any progress on the several international legal cases regarding the genocide perpetrated against the Rohingya community?

To this date, despite extensive documentation, widespread outcry among the international community, and an ongoing case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Burmese military has yet to face any consequences for its actions.

In 2012, 2015 and 2016, Rohingya refugees had to flee to Bangladesh, with another significant surge after a violent ‘clearance operation’ by the Burmese army in August 2017. Over one million Rohingya seek refuge in Bangladesh, which bear the burden of taking care of them. It’s crucial to recognize that the Rohingya crisis originated in Myanmar, and not Bangladesh.

While Bangladesh is not a signatory of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, international human rights principles affirm the Rohingya’s right to return to Myanmar. But the international community hasn’t pressured enough Myanmar for justice and rights restoration for the Rohingya. Instead, Western governments have increased diplomatic and economic engagement with Myanmar, rather than imposing effective sanctions.

Since the junta staged a takeover coup in February 2021, women have emerged as symbols of defiance and as key leaders of resistance efforts inside the country as well as abroad. Over the last two years, the military has murdered over 300 women, arrested and detained at least 3400, and tortured hundreds of thousands more. The army, sadly infamous for perpetrating rapes in full-impunity, continues to intensify its use of sexual and gender-based violence across the country’s war zones, as well as in prisons and detention centers against activists or partakers in the Civil Disobedience Movement. It serves as a reminder that no woman or girl in Myanmar is safe under the patriarchal, misogynistic, and criminal junta.

Where can Rohingya people currently go?

Although Bangladesh has been recognized as a temporary haven for Rohingya refugees, many people are trafficked out of those camps. Due to the socio-economic and safety in both Bangladesh and Myanmar, many take risky journeys on boats or across land. Whilst some make it to their destination, many are exploited, abused, and become trafficked. More than one million Rohingya live in the refugee camps of Bangladesh with frequent reports of child abductions. When deciding to flee the camp, many refugees are given false information about the journey, destination, and costs.

There are no durable solutions: Approximately three-quarters of a million Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh in 2016 and 2017 due to mass violence perpetrated predominantly by Myanmar security forces. Some of these Rohingya refugees have lived in Bangladesh since the 1990s. As such, multiple generations of Rohingyas have been born in the refugee camps.

Since 2017 the Rohingya have been registered by UNHCR. They are currently provided with biometric cards which are issued jointly by the Government of Bangladesh and UNHCR. They are not formally recognized as refugees, but instead are referred to as ‘Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals.’ As of late, there are no formal pathways for Rohingyas to be naturalized or acquire citizenship over the long term in Bangladesh or Myanmar. Although births are registered, they are separate procedures from citizens of Bangladesh.

Other durable solutions to protracted displacement for Rohingyas are also few and far between. Large-scale voluntary repatriations to Myanmar since the 2016-17 exodus have not been possible despite the bilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) in place between Bangladesh and Myanmar. Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are insistent that they should be able to return directly to their lands and should be provided with citizenship.The unstable conditions in Rakhine State are not conducive to safe and sustainable returns. There are continued rights abuses and conflicts between the junta forces and the Arakan Army.

Between 2006 and 2010, 940 Rohingyas were resettled from the camps to third-countries. The resettlement programs were then halted by the Bangladesh government, due to concerns that they would create a ’pull factor’. Recently exit visas for resettlement in third-countries have been issued again to a small number of refugees at risk in the camps.

Rohingya people desperately want to leave Bangladesh because it is not their land and they have no intention to stay forever. Bangladesh has had to deal with the influx of Rohingya refugees since the 1970’s. How long can they take this burden while they have to resolve their own problems too? Bangladesh’s generosity cannot be denied because it never pushed back Rohingya people but in the future the country will be forced to take action for its own safety. As per international law, Bangladesh has the full authority to negotiate for a fairer shared responsibility of hosting refugees with countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and India.

What are the future projects you want to achieve?

Currently, I am facing various challenges as the founder of a women-led organisation in Cox’s Bazar. As a feminist, I have always focused on women’s issues no matter who they are or where they belong. But I have realized that women who cannot have their own voice to speak freely become a burden solely due to those circumstances.

I hope to continue running my organization, which although small, is a model for other women abroad. My main commitment is to ensure women’s rights and stop all kinds of discrimination and to make women aware of what they deserve.

© Portraits of women in Cox’s Bazar were taken by photographer and poet Shahida Win.

➽ You can follow her work with the Rohingyatographer collective and read her interview on Visual Rebellion Myanmar