Unsettled Waters: Irrawaddy Dolphins Caught in the Crossfire

By Harry

MATTAYA, MANDALAY REGION // When noon arrived U Aung San grabbed his lunch box and headed down to the Irrawaddy River on the west of his village. A fisherman in his fifties, he moved along the river’s edge with skill, gently tapping his boat. Within a few moments, a dolphin swam up beside him. Aung San waited, watching as the dolphin raised its tail, to signal when to cast the net into the rippling water. As the dolphin struck the water’s surface, Aung San tossed his net just in time to catch the fish below. Pulling up his catch, he felt his net full of fish.

“The fish can always be caught in piles. It’s easy. Some even weigh 24, 25, or 28 pounds per fish,” he said.

By sunset, he would earn around 10,000 kyats from selling the fish.

***

This nostalgic scene belongs to the past – before the military coup in 2021. Nowadays each time Aung San goes to the river, the dolphins come far less easily. The familiar, symbiotic rhythm of fishing with dolphins has changed. Both fish and dolphins are fewer, and it is much harder for Aung San to sustain his family.

He lives in the Irrawaddy Dolphin Protected Area No.1, located in Mattaya Township, Mandalay Region. Over the past three years, he has witnessed intense fighting between the coup-led military and the People’s Defense Forces. Along the 350km stretch of the Irrawaddy River – from Mandalay to Katha in the Sagaing Region – this conflict has had significant impacts for people and wildlife.

Illegal electrofishing (using electric shocks in the water) and artillery shelling have dominated life over the past three years, and local residents report a resulting and tragic loss of dolphin life. 79 living dolphins were observed in 2020 a census conducted by conservation organizations and the Fisheries Department. Due to the chaotic situation following the military coup, however, at least six Irrawaddy dolphins have reportedly died.

Boat operator Htein Lin, who navigates the Irrawaddy, shared that by mid-2023 he had personally seen four dolphin carcasses on the stretch between Mandalay and Katha, three of which were female.

“These were young dolphins, about seven or eight years old. Some were badly decomposed, while others showed injuries or signs of electrocution,” he said. Dolphin observers and local residents say that although the current situation is difficult to analyze, they may have been killed by electrical shock fishing, gunfire, and artillery firing along the river.

According to the records obtained by our journalist to back Ko Htein Lin’s observations, a dolphin was disfigured and killed near the village of Pay Thone Sal in Mattara Township on March 5, 2023. Another incident occurred in August 2023 near Nyaung-U. The latest one was found in the town of Kathar on January 12, 2024.

Global Dolphins, Local Benefits

Irrawaddy dolphins are found not only in Myanmar but throughout the region in Viet Nam, Cambodia, and Laos, which are part of the Mekong Basin. The dolphins’ name derives from the Irrawaddy River in Burma where they were first discovered. Here, they are most well-known for their distinctive tradition of fishing alongside humans.

“Our dolphins have lived and worked with us for generations, in an intangible cultural bond,” said Tayza, an environmental activist focused on river conservation. “The fishers and dolphins have developed a cooperative relationship, each learning from the other and passing down these skills through generations, making the two inseparable.”

The dolphins’ fishing traditions were recognized by UNESCO in 2014 for the preliminary list of World Heritage Sites. The Irrawaddy River has been included in seven stunning Myanmar sites designated by UNESCO due to the presence of these Irrawaddy dolphins.

Irrawaddy dolphins live about 30 years and, typically, a female gives birth to one calf annually, breastfeeding it for up to 18 months while caring for it for three years.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges

Irrawaddy dolphins are recognized as endangered, prompting efforts by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and the Fisheries Department, to collaborate in creating protected areas for their conservation. In 2015, the 72-kilometre river stretch from Min Kun to Kyauk Myaung was designated as Protected Area No. 1. In 2018, another 117-kilometre zone was added. During these operations, the Fisheries Department and the Maritime Police undertook operations against electrofishing.

Before the 2021 coup, the Irrawaddy Dolphin Conservation Zone supported a thriving tourism industry, attracting approximately 1,000 international visitors each year. This influx of tourists provided valuable income and job opportunities for young people, fishers, and local vendors.

“I used to run dolphin-watching trips two to three times daily, making a profit of 20,000 kyats after fuel costs, totalling around 500,000 kyats a month,” said boat operator Htein Lynn.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, conservation efforts persisted, with travel companies still working to protect dolphins despite the absence of tourists. However, after the coup, tourism ceased, leaving conservation efforts struggling for survival.

Abandoned Conservation Efforts Amid Escalating Conflict

Following the 2021 coup, conservation organizations can no longer safely access dolphin protection zones.

“Until September 2021, villages along the Irrawaddy River were accessible. However, after that, both the land and the navigation were no longer secure,” said a conservation manager.

Dolphin watchers who can no longer access the land now collaborate with local fishers to document the dolphins’ situation to the best of their ability. Nevertheless, obtaining accurate knowledge of the situation is not easy on the ground.

Fighting has intensified along the Irrawaddy River. Amid heavy artillery attacks and the strafing and razing of entire villages, many residents have been forced to flee, leaving once-bustling villages deserted.

U Aung San has been able to return to his village for only a few months after crossing the river last year and fleeing to Sagaing Township. However, the threat of military forces and jet fighters prevented him from staying. Now, he lives on a sandbank across a stream from what remains of his village, where most of the 500 homes were burned, leaving only about 20 homes remaining. With the military stationed on the eastern bank, Aung San reports that their gunfire frequently comes across the river, with stray bullets striking its waters, further endangering the dolphins. Observers continually note that nearby explosions can also harm dolphins, in some instances fatally.

While the coup’s military authorities announced renewed dolphin-watching tours earlier this year, locals and visitors alike remain wary of the area.

“The Fisheries Department is unwilling to enter the river, and no tourists have returned,” Htein Lin explained. Many motorboat operators, including Lin, have lost their livelihoods, selling their boats to survive. “We used to have about 40 boats, but now only around 10 remain.”

“At Mandalay’s 26th Street Harbor, the personnel have downed tools, too afraid to monitor the river,” said Htein Lynn.

He lost his income with no one to hire his motorboat since the coup.

The tourism manager expresses concern that the future of the Irrawaddy dolphin population and their unique bond with humans may be at risk. “With the collapse of the entire ecosystem, it’s possible the dolphins are disappearing without our knowledge. If stability ever returns, we may find it too late to save them” .

More than a thousand kilometers to the west, in the eastern Indian state of Odisha, the Irrawaddy dolphin population is thriving according to the 5th Flora and Fauna survey carried out by the Chilika Development Authority. One of the flagship species inhabiting the Chilika lake, the Irrawaddy dolphin is protected under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972, CITES, and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. The report has revealed that the population of Irrawaddy dolphins could be in the range of 155 to 165. Open to visitors, the brackish water lake is part of a national park that “has become a safe home for the dolphins whose distribution range at present has remained limited to Asia – from Chilika to Indonesia.”

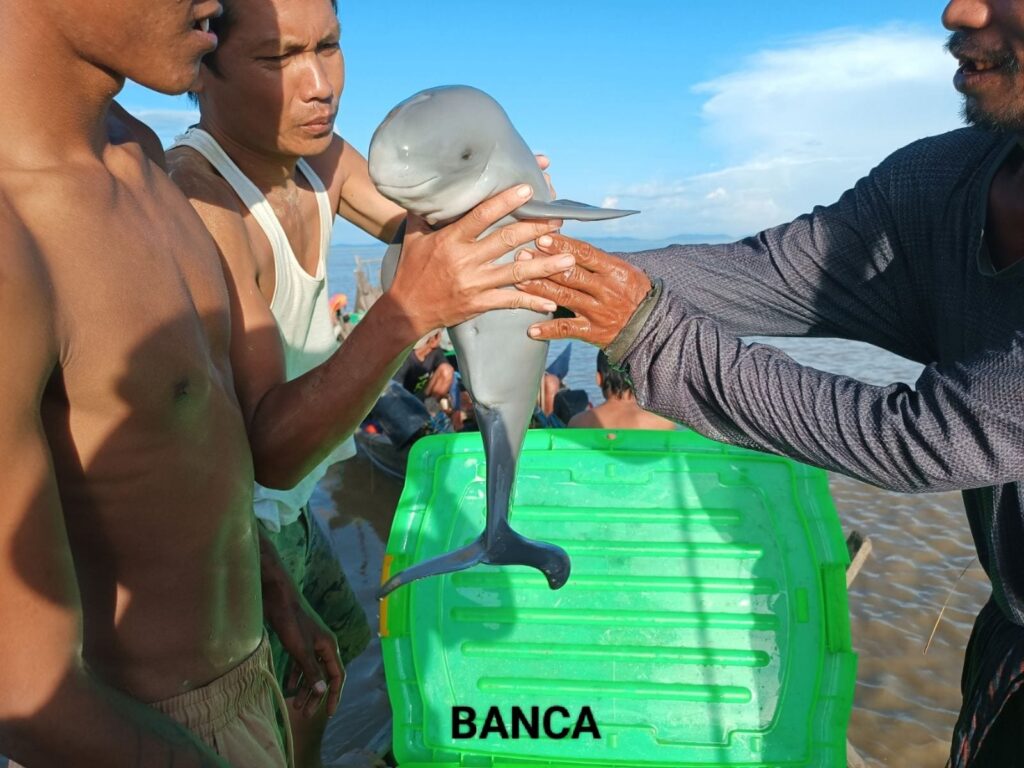

Back in Burma, local conservation organizations continue to save anything and anyone they can amidst the mayhem. This October, the Biodiversity And Nature Conservation Association (BANCA-BirdLife Myanmar) saved a baby dolphin and released him in the deep sea.

- All names have been changed for safety reasons

-

The initial version of this story was published in May 2024 by Myaelatt Athan, the Burmese-language media covering central and upper Burma. It has been updated and translated to English by our team, as well as in French for Mediapart.