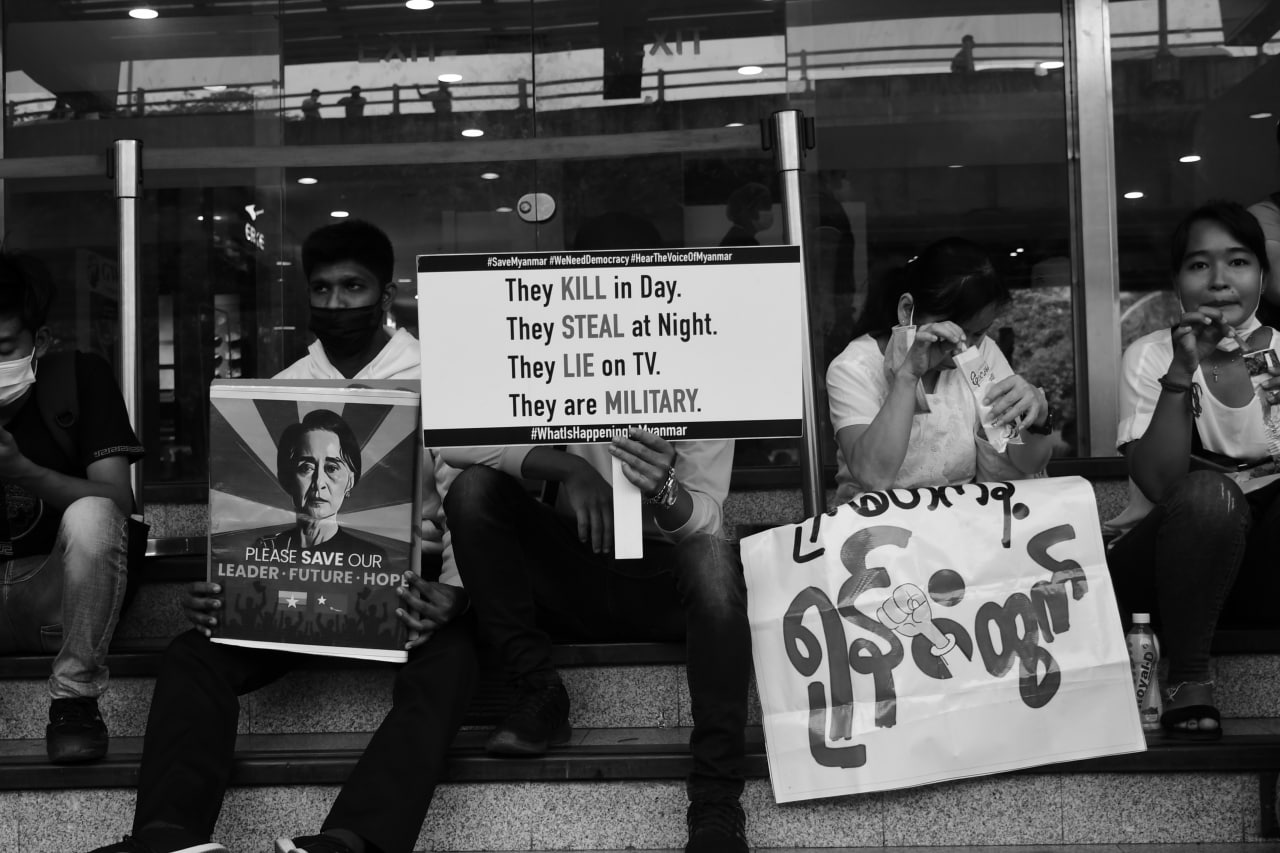

AUGUST 1st, 2022 // After the military coup on February 1st, 2021, journalists were among the first to be hunted down along with opposition politicians, social workers and activists. All independent media outlets have been stripped off their operating licenses. Two newspapers and two TV channels controlled by the military can still function openly while the rest of the media landscape has been forced underground or in exile. In 2021, Burma became the country that imprisons the most journalists after China and sits now at the 176th rank out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.

© Photograph by YGN108 / Visual Rebellion Myanmar

Dozens of reporters have been arrested and four have been killed by the State Administration Council (SAC), the regime led by junta leader General Min Aung Hlaing.

We remember them.

On December 10th, 2021, Soe Naing, a graphic designer and freelance journalist, was arrested in downtown Yangon while covering a “Silent Strike” (see our article) against military rule organized on International Human’s Rights Day . He died a few days later under torture in military custody and is considered the first journalist killed by the SAC since the coup. After his shocking death, most reporters stopped covering events from the streets.

On December 25th, 2021, Federal News Journal editor and poet Sai Win Aung, known as A Sai K, was killed by an artillery attack as he was covering fighting and living around Lay Kay Kaw, a haven village for journalists and activists in southeastern Kayin State’s Myawaddy Township on the Myanmar-Thai border. His friends tell his story in “Walking Through Darkness”, a powerful documentary on the dire situation Burmese media have been plunged into since the military seized power.

On January 9th, 2022, the body of Pu Tuidim was found in Chin State’s Matupi Township amid fighting between the military and the resistance forces. A couple of days earlier, the founder of the Khonumthung Media Group was abducted by soldiers with at least nine other people, who were used as human shields before being executed.

On July 30th, 2022, the family of photographer Aye Kyaw was informed of his death after he was arrested at 2 a.m. that day on the grounds of stashing weapons at his home in Sagaing city, none of which was to be found. His body was marked by bruises on the ribs and the back, indicating extreme torture. Aye Kyaw’s photos of anti-coup protests were circulated on social media and shared by pro-democracy politicians and local media.

His murder sends the recurring message of the military to the public that they have the power to kill anyone. Since the February 1st, 2021 coup, 158 media workers have been arrested, for some tortured, and 89 are still currently detained according to Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), and the junta’s legal harassment and clampdown against reporters is going on unabated.

On July 29th, 2022, journalist Maung Myo, also known as “Myo Myint Oo,” was put on trial and sentenced to six years in prison for allegedly violating Section 52(a) of the Counter-Terrorism Law based on possessing pictures and interviews of “resistance forces”. Maung Myo’s conviction follows the recent prosecutions of Aung San Lin and Nyein Nyein Aye, who were sentenced to six years with hard labor for “incitement” and / or “terrorism”.

The journalist was accused of promoting instability in Myanmar by posting photos of anti-regime protests and the junta’s regular use of violence on social media.

A dozen of female reporters are still imprisoned, particularly in Shan State, and some were arrested along with members of their families.

We don’t forget them.

On August 15th, 2021, Htet Htet Khine, well-known lead presenter of BBC Media Action’s national peace television program, Khan Sar Kyi (Feel It), was arrested at her hideout in Yangon and has been detained ever since. She was condemned with two three-year sentences with hard labor in September 2022.

On December 13rd, 2021, Nang Win Yi, Nang Nang Tai, and Tin Aung Kyaw, three reporters from Kanbawza Tai, based in the Shan State capital of Taunggyi, were sentenced to three years in prison for incitement. Sai Sithu, Nang Nang Tai’s brother, was also sentenced because he was in his sister’s house at the time of their arrest.

On December 30th, 2021, Mya Wun Yan, editor-in-chief of the Than Lwin Thway Chinn media outlet based in Taunggyi, Shan State, was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment under Section 505 (a) of the penal code. She had been arrested on July 20th, 2021 with her two daughters.

On April 7th, 2022, Lway M Phaung, a 20-year-old former video journalist from Shwe Phee Myay News Agency, was sentenced to two years in prison in Lashio on trumped-up charges. On September 26th, 2021, she was arrested by dozens of soldiers at her home and spent more than six months in pretrialdetention. She is one of six journalists who have remained in prison in Shan State since the coup, including four women.

Five foreign journalists have also been arrested since the coup, with four released after diplomatic negotiations.

Yuki Kitazumi, a Yangon-based Japanese freelance reporter, was released after a month of detention mid-April 2021.

Nathan Maung, a U.S. journalist who co-founded Kamayut Media was detained on March 8th, tortured and released on June 15th, 2021.

Daniel Fenster, a U.S. editor for Frontier Myanmar was arrested on May 24th while attempting to leave the country at Yangon airport and released on November 15th, 2021.

Robert Bociaga, a Polish journalist was arrested while covering street protests on March 11th, 2021 and released two weeks later.

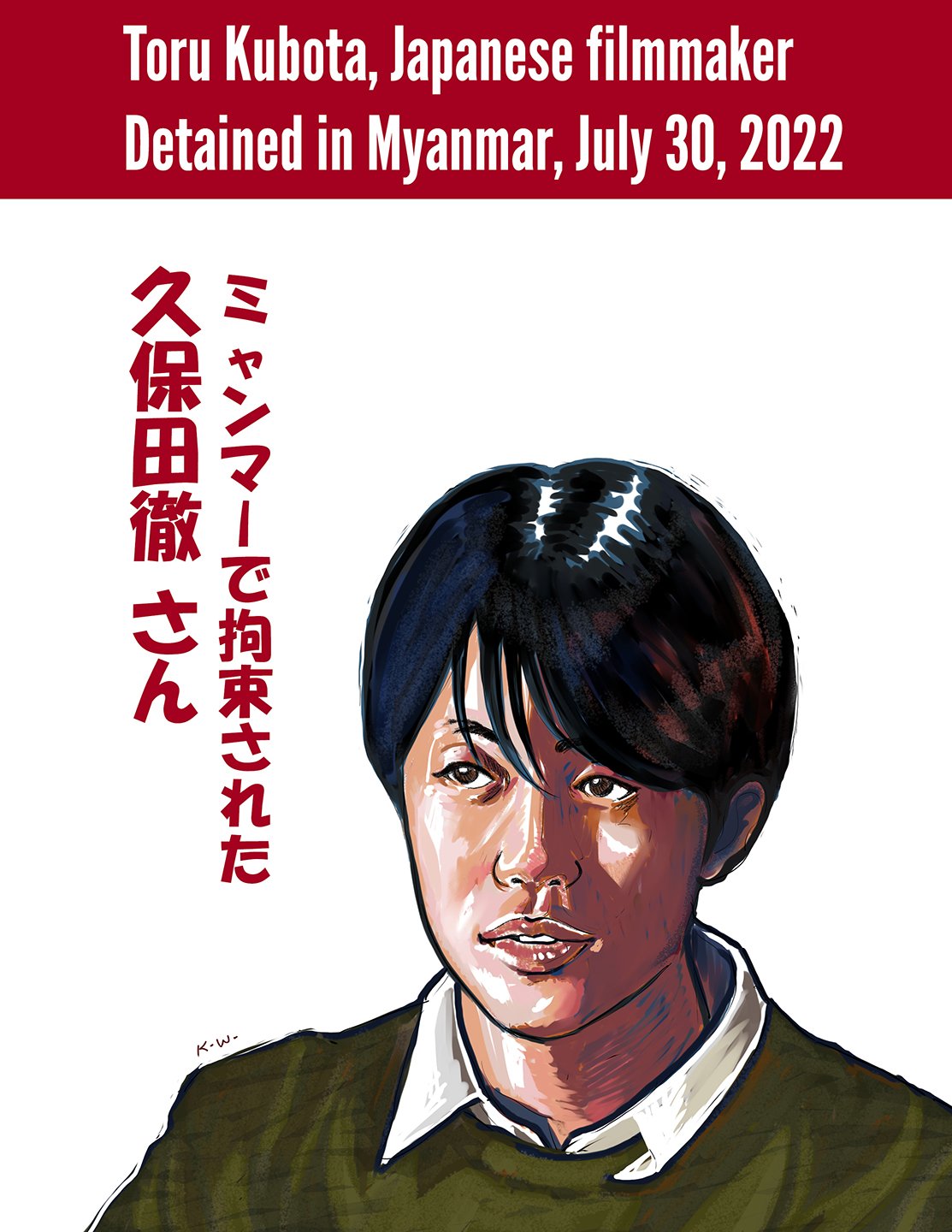

Turo Kubota, a Japanese documentarist, was arrested for filming a demonstration in Yangon on July 31st, 2022 and remain in jail to this day. A photo of Kubota holding a protest sign circulated among pro-military accounts online and was used by the authorities to justify his detention, according to fellow journalist Yuki Kitazumi as well as Typ Fone, leader of the Yangon Democratic Youth Strike. In October 2022, Kubota was condemned to ten years in prison for violating sedition and communications laws in a sham trial.

For journalists in Myanmar, a scarcity of choices remain: hiding underground in-country, being arrested with the risk of torture, killing, or a lengthy jail sentence, having their relatives being kept hostages in military bases or going into exile, mostly in Thailand or in Western countries for those who have the resources to apply for resettlement.

Despite the terror and the pain, hundreds of them continue to research and write about the post-coup daily life to remind the outside world of human rights atrocities, environmental disasters, fighting between resistance forces and the junta soldiers, as well as the complicity of foreign capital in feeding the bloodshed.

Visual Rebellion Team is committed to helping our team of journalists stay safe and continue to report on what is happening in Myanmar, as the public needs reliable information more than ever.

Please consider supporting our work.

© Photograph by YGN108 / Visual Rebellion Myanmar

BACK TO TIMELINE