Hope for international support rise as US Senate passes Burma Act Bill

United States// After many years of attempting to pass a version of the “Burma Unified through Rigorous Military Accountability Act of 2022” (as known as BURMA ACT), both houses of the U.S. Congress have finally passed the bill. This welcomed development comes after multiple failed attempts in 2019 and 2021.

On December 16th, President Biden signed the bill, making it an official law. The BURMA Act is part of a larger bill called the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, that sets the future expenditures for U.S. defense budget. These expenditures can be in the form of finances or resources. It could also involve the deprivation of expenditures if certain conditions are not meant. The bill has multiple parts and the BURMA Act is only a small part of this larger policy.

What is in the Burma Act?

The BURMA Act demands the U.S. government allocate some funding to humanitarian causes and groups within Myanmar. Also, the act provides for some ability to sanction the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE) and other junta-linked businesses conglomerates.

However, in order to pass the bill, some parts of the previous versions were taken out, meaning it has some limitations. The sanctions on the military junta are limited in nature since they have a loophole that allows the U.S. company Chevron to continue to operate in Myanmar. This contrasts with calls in the initial version of the act to ban U.S. energy companies from operating in Myanmar.

Also, the act fails to explicitly condemn the persecution of the Rohingya people. This version of the act was a compromise between Republicans and Democrats. Previous acts failed due to the refusal by some Republicans to include condemnation of the Myanmar government’s Rohingya policy. This was particularly true with Mitch McConnell, the former leader of the U.S. Senate. He was against denunciation of the persecution of the Rohingya population because it would involve criticizing the ethno-nationalist sentiments of Aung San Suu Kyi.

He considers ASSK an ally and he views criticisms of her by a global power as potentially weakening her position within the country. This issue was overcome after many proponents of the BURMA Act thought it was less necessary for the act to directly address the Rohingya situation due to the state department officially recognizing the situation as a genocide.

Additionally, the act is not vague in the anti-junta forces it seeks to support. It specifically mentions the National Unity Government (NUG) as a group it seeks to empower and includes allowing the U.S. government to directly negotiate with the NUG, instead of having to engage with an active human rights violator like the current junta. The NUG is a political coalition made up of former government officials that were ousted during the coup. As the situation currently exists, the NUG is the most likely alternative to replace the junta if a democratic change were to happen so the NUG must gain the support of foreign powers. Allowing negotiations with the NUG is an important inclusion because no countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are negotiating with the NUG to this day.

Beyond Myanmar, the act also condemns supporters of the military junta. This includes both China and Russia. This is an important aspect of the policy, but the efficacy is limited. It is highly unlikely the U.S. would severely antagonize these global powers over a country like Myanmar. Myanmar does not possess enough U.S. material interest to motivate the government to engage in a serious conflict with China or Russia.

Who is behind the Burma Act?

The passing of the BURMA Act was only made possible by a coalition of advocates for human rights and democracy in Myanmar. An early grassroots organization involved in the movement within the U.S. was the Free Burma Coalition, which has existed for over two decades. This organization grew by establishing chapters near college campuses and urban areas. These chapters organized demonstrations that advocated for blocking US trade relations with the Myanmar authoritarian regime in the 1990s. The organization’s slogan was “When spiders unite, they can tie down a lion.” They were one of the crucial organizations in the anti-junta movement that led to a U.S. company like PepsiCo divesting from Myanmar in 1996. This broader anti-junta movement led to the George Bush administration placing an import ban on Burma in 2003. Though the movement continued, it had since lost some of the spotlight it had in the late 90s.

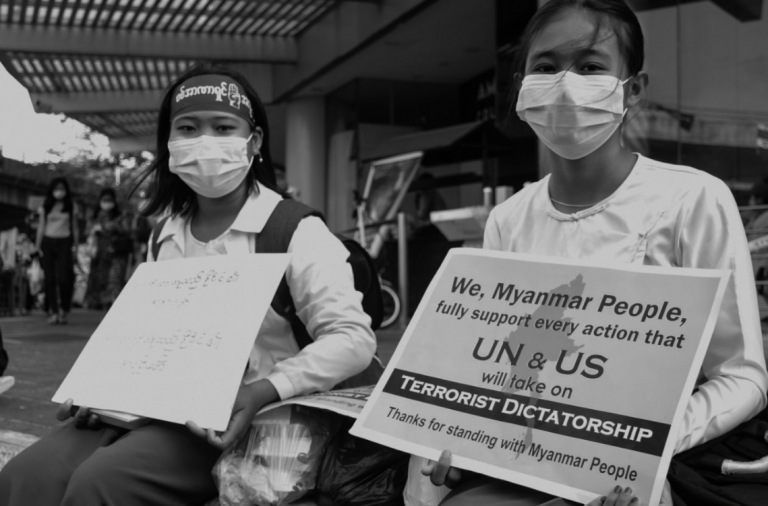

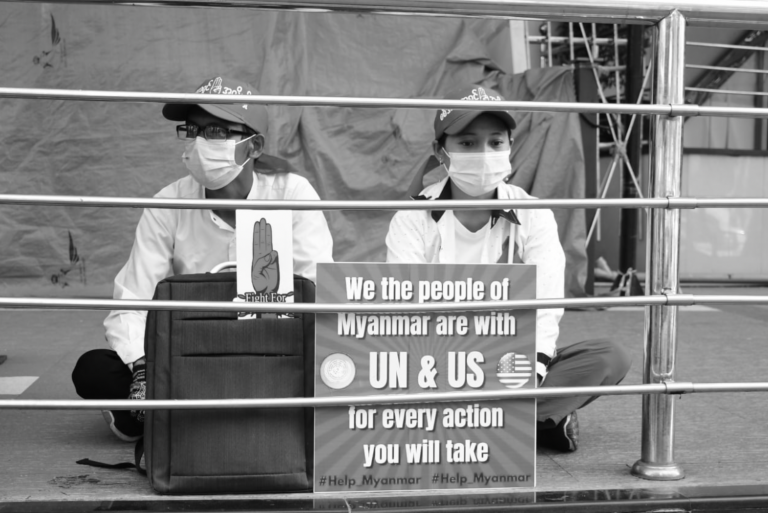

It was not until the late 2010s and early 2020s, right before and after the coup, that there was enough momentum to get the BURMA Act passed. A group responsible for this movement is the US Advocacy Coalition for Myanmar. The organization is made up of millennials, Generation Z, and their age group allies. They made their voices heard by attending meetings with 70 senators and building a relationship with the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

Another group responsible for the passage of the bill is the Burma Advocacy Group which consisted of minority religious and ethnic groups such as the Chin Baptist. The group represents a diaspora population living in the U.S., politically activated by the persecution their group encountered in northern Myanmar.

Why did the Burma Act pass?

The BURMA Act is part of a broader bill, which many human rights advocates are critical of. The National Defense Authorization Act is seen as further empowering the U.S.’s ability to support or directly engage in human rights violations in other areas of the world. For example, the law allocated about $400 billion to private U.S. military contractors. These contractors lack strong government oversight. They often provide personnel or armed support to regimes engaging in human rights abuses globally. However, the BURMA Act section of the bill does not include the sending of U.S. weapons to Myanmar. There is tension between this specific aspect and the broader bill, which human rights advocates should keep in mind when evaluating this bill.

Though the act contains limitations, it is an important foundation. It provides a template that can be improved upon. It also puts pressure on other countries in the ‘Global North’ like Europe to adopt similar policies. This will only be possible by internal movements in America and other countries continuing to put pressure on their governments to support anti-junta movements within Myanmar.

What about other non-Myanmar legal systems?

Other than the BURMA Act, the use of courts in other countries outside of Myanmar has been another way to legally condemn the situation inside. The principle of universal jurisdiction is the idea that some human rights violations are severe enough that any country can investigate and potentially prosecute these violators. Victims of human rights violations by the Myanmar government are testifying and filing lawsuits in foreign countries. These lawsuits were for violations that occurred after the coup in 2021 and for violations that occurred during the 2017 genocide against the Rohingya Muslim community.

One of the more notable lawsuits is a case filed by Southeast Asia-based human rights organization Fortify Rights. On January 24th, 2023, they filed a lawsuit on behalf of 16 plaintiffs with the Federal Public Prosecutor General of Germany. The lawsuit includes alleged claims of sexual assault, torture, extrajudicial killings, kidnappings, and property destruction by the military junta. Some of the plaintiffs have shown a public willingness to testify against the Myanmar junta. All the plaintiffs describe significant mental or physical impact from these experiences though they no longer live in Myanmar.

One of the testimonies made publically available by Fortify Rights is from a 51-year-old woman. A group of soldiers and a civilian mob attacked her village. Soldiers entered her home and beat her, while she heard her daughter-in-law being raped in another room of their house. Due to the attack, she lost seven family members and many of the houses around her were burned down.

As of now, German legal officials have acknowledged receiving this lawsuit, but no other comments have been made. Before the lawsuit enters courts, an extensive investigation will take place in order to justify an indictment.

Similar lawsuits are being filed in other regions of the world, such as in Argentina and Turkey. Officials have decided to investigate claims of Crimes Against Humanity brought to Argentinian courts by the London-based Burmese Rohingya Organisation. In Turkey, the Myanmar Accountability Project (MAP), has brought a case to court accusing the junta of a systemic torture program. Furthermore, transnational legal institutions such as the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice, are investigating Myanmar’s generals.

This is not an unprecedented mode of action being taken by those seeking justice in the courts of other nations. For example, the Argentine legal system engaged in an investigation of the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War and Francisco Franco’s regime for evidence of human rights abuses in 2010. Though not common, this approach does have some legitimacy based on precedence.