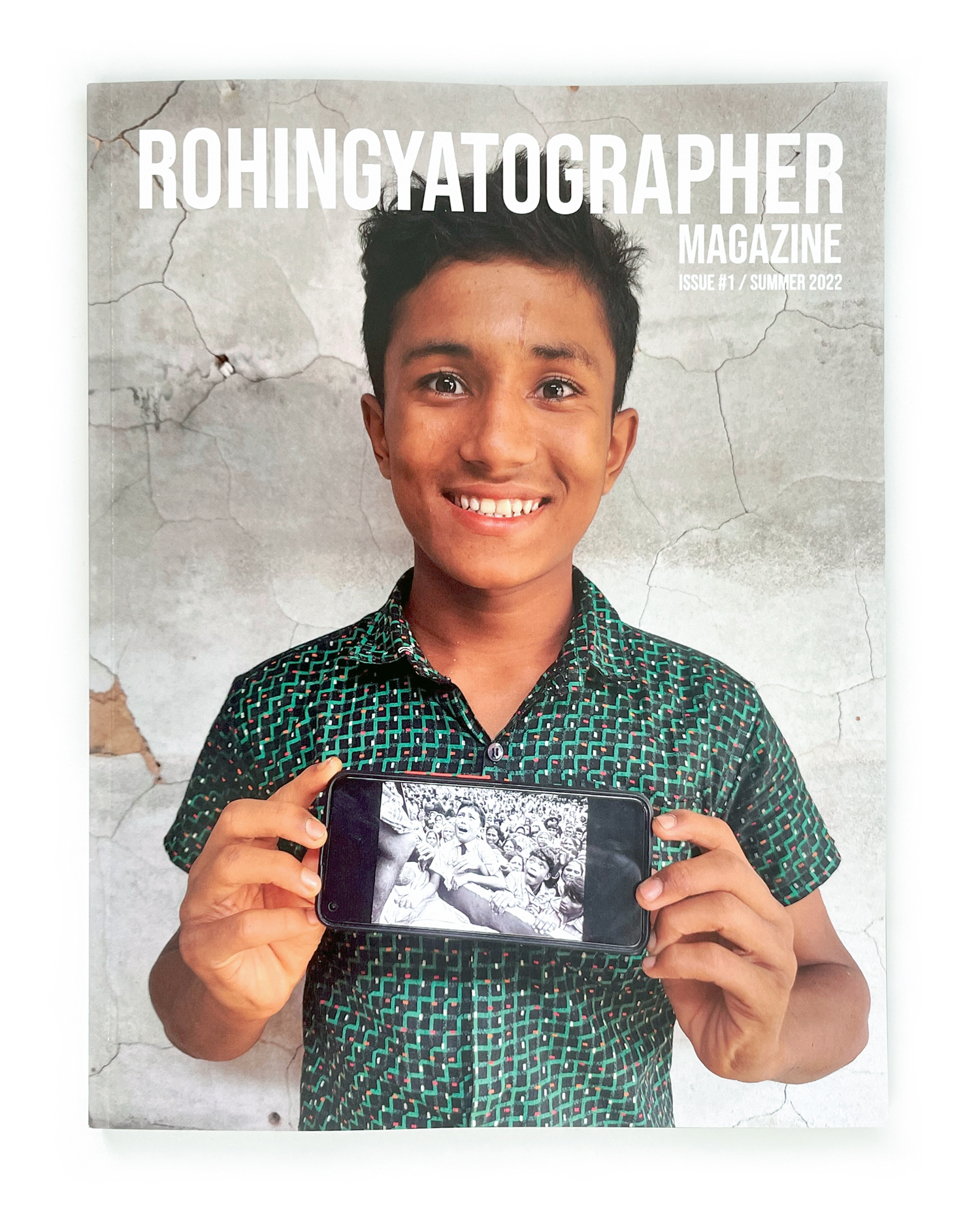

In the summer of 2022, a collective of Rohingya photographers living for years in the Kuputalong-Balukhali refugee camp in Bangladesh published their first photography magazine. As the genocidal campaign against the formerly Rakhine-based Muslim community happened five years ago, Visual Rebellion Myanmar interviewed three key members of the “Rohingyatographer” magazine team about their motivations, challenges and ambitions.

By Sian Mc Allister / Visual Rebellion Myanmar

By Sian Mc Allister / Visual Rebellion Myanmar

On the edge of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, the Kuputalong-Balukhali expansion site is the world’s largest refugee camp and is inhabited mostly by Rohingya people. The Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic group who lived mainly in Rakhine state, Myanmar, where they have been stripped from their citizenship rights since 1982. From October 2016 and then August 2017 onwards, Buddhist Rakhine nationalists and later the Burmese military launched a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing and forced deportation, which has sent a million Rohingya people running for their lives across the Naf River to seek refuge in Bangladesh.

For more context on the politics of inclusion and exclusion in Myanmar, read the Special Issue on the Rohingya by the Independant Journal of Burma Studies.

More than five years later, life is hard and uncertain for most people trapped in those unsafe camps and for the many other displaced Rohingya refugees across the world. In an effort to make sense of and raise awareness of their situation, a team of creatives based in Balukhali camp set up ‘Rohingyatographer’, a photography magazine documenting their experience as refugee, but also artist and human being. In their words, Rohingyatographer allows the Rohingya community to be known not only for their marginalization but also for their ‘creativity, talent, and aspirations for the future’. The magazine and their platform also stresses the importance of using photography and art as education tools for the Rohingya, as over half of the refugee population are children. Provided with the means to tell their stories, they are empowered with self-expression and a range of other skills.

© Photograph by Omal Khair

© Photograph by Omal Khair

Many were also involved in the establishment of the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre, an institution located at the heart of the camps dedicated to chronicling the community heritage and to educating the youths that are born outside of Rakhine State about their culture and history.

© Photograph by Sahat Zia Hero

An ongoing International Court of Justice (ICJ) investigation of Myanmar in Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide has been cleared to proceed, with Gambia initiating the prosecution of the Burmese military junta for the genocide of the Rohingya people. New evidence of war crimes committed in Myanmar have also emerged.

In the context of this recent legal progress as well as the five year mark of the Rohingya mass exodus from August, 25th, 2017, Visual Rebellion Myanmar wished to express its support by highlighting the Rohingyatographer project.

Sahat Zia Hero is the founder, editor and photographer of Rohingyatographer magazine. In 2012, he was excluded from attending university and in 2017, he escaped the genocide in Myanmar. His photography has been published internationally by The Guardian, UNHCR, etc, and was exhibited at the 2021 Oxford Human Rights Festival. He also works at the Rohingya Cultural Memory Center and writes poetry.

Shahida Win is a female photographer and poet for Rohingyatographer. She was born in the Irrawaddy region, Myanmar, and initially worked as an interpreter for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), before following her passion for journalism. Since fleeing Myanmar in August 2017, she has worked as a volunteer for MSF and other NGOs.

David Palazon worked as the curator of Rohingyatographer, as well as a mentor for its founders and contributors.

With Sahat, Shahida, and David, we discussed the setting up of the magazine, what life is like in a refugee camp, and the importance of art in the preservation of human rights and the fight against oppression.

Sahat Zia Hero

Sahat, what inspired you to create Rohingyatographer? What were the most difficult challenges you faced when setting it up?

I love photography, documenting our memories and lives in the camp. I fear that people will forget and not know about our experiences so I share the truth on social media. I share our photos on Google, Twitter, and Instagram. Many people began to follow us so I thought about making a publication so we can touch an even wider audience about what we are going through. It is also good because we reached out to and included young photographers from the camp.

The greatest difficulty was that we cannot buy photography equipment and devices and we can only use our phones. Anyhow, we still take photos everyday using them. Also we are working on this project as volunteers and it is very difficult sometimes to get funding. We often have no internet data, no Wi-fi, or electricity. Those are the biggest challenges.

How did you and the other photographers learn photography?

Most of us learned in Myanmar. I had a digital camera in Myanmar before 2017. I used to take photos everywhere, when I went out with my friends to a picnic or to the forest, also at weddings and parties. When we arrived in the camp, most of us who took photos before met people, mostly journalists, from around the world who came to the camp and we worked with them. There are lots of videos online from organisations like Amnesty International and the people behind those taught us how to document, to make videos and photographs, and to share our stories. But we have not learned from courses or workshops.

Does the magazine involve any photographs from Rohingya people who live in Myanmar or is it just from people living in the refugee camps?

The photographers all live in the camp. We had some photos from our lives in Myanmar but most of us lost our memory cards and we could not bring anything from Myanmar. While in Myanmar, we could not use internet or mobile phones and using a camera was very risky during that time. But we have some photos from refugees who were able to bring their photos. We used these photos of previous lives in Myanmar, especially those highlighting the genocide and arrests during the military’s operations. For example in the magazine, you can see one photo of a photographer with marks of gunshots on his back sustained when he fled Myanmar and we wrote about his story.

Can you explain how, for you, creating and sharing art is a way for you to oppose the Burmese military’s treatment of the Rohingya people?

We are refugees because of a genocide conducted by the military. They are the main perpetrators and they killed and tortured people, and raped Rohingya women. They caused us to flee from our country. There are a million Rohingya people living in refugee camps. It’s really important to highlight who are the perpetrators behind the genocide. Our objective is to highlight our crisis and to show the international community what is happening and to let them know that this genocide and persecution is still going on even without publicity. To also call upon the international community to help make changes to the Myanmar government and improve the situation of the country.

As well as the communicative quality of art, it has incredible value for collective memory. Can you tell us more about the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre and its mission?

The center is to show locals the culture, heritage and identity of the Rohingya people. This includes explaining the fishing and farming culture and preserving cultural objects, to keep alive our culture, especially for the children born in the camps. We keep reminding people what happened and show the world that the Rohingya people have their own history.

I read that you were excluded from university and then fled Myanmar to live in Cox’s Bazaar. If you are comfortable to do so, would you be able to describe that experience to me, and your current life in a refugee camp?

In 2011 and 2012 I attended Sittwe University in Rakhine State. To attend this university I faced a lot of challenges like having to apply for a passport and for approval letters from lots of departments such as the police station and many other government authorities. I had to go to town to get the passport from immigration officers as I needed this document to travel out of my district to university. On the way to university there were lots of checkpoints where we had to show these documents. They would only check Muslims, and especially the Rohingya. At university, I faced a lot of discrimination. I wanted to talk and sit with the other students but they were not fair and hated us and would not talk to us or defend us even though we were in the same class. Even the teachers and the lecturers used derogatory names for Rohingya people.

After the riots in Rakhine state in 2012, there was a lot of violence. Education could no longer continue for Rohingya people. As I was coming back home in June, I was arrested by the police at a checkpoint before entering my village. I was beaten for a long time and kept in custody for three days. I was arrested for traveling during the riots even though I had all my approval letters. I did not leave my village after that and I couldn’t see my friends outside my village. I supported my father by fishing, like most Rohingya people in Rakhine state did. I bought a computer and a smartphone, which was illegal for Rohingya people to have, and I learned how to use them by watching Youtube tutorials. I could only use the smartphone in limited situations so I went to the jungle to use it. My village was very close to Bangladesh so I could use the Bangladeshi Internet network. I also had a camera so I started photography during this time.

In 2017, the Rohingya villages were suddenly destroyed. My village was burned and everyone ran away from the genocide, along the roads that led to Bangladesh and we reached the border and came into the refugee camp. It took about twenty minutes to get there. The day was August 25th and one million Rohingya refugees left since then. The military surrounded each village and shot anyone they saw and raped the women. Ten people in my village were killed on that day including my neighbour’s son who I knew very well.

Living in the camp is very difficult, especially without education opportunities and freedom of movement. Our lives have totally changed. The camps are very crowded, there is very limited space, especially for families. Sometimes ten members in one family have to live in one small unit.

© Photograph by Sahat Zia Hero

You have worked for the Danish Refugee Council and for several international media outlets thus are very involved in communicating about the Rohingya crisis to non-Burmese people. What is the most important thing you would like the rest of the world to know about the position and experience of the Rohingya people, especially in Cox’s Bazar?

We completely lack safety, it is not safe for Rohingya people anywhere right now. So the most important thing is for the international community to call on world leaders to help us return to our country and receive reparations. We have spent five years in Bangladesh, and now the Bangladeshi government is finding it difficult to help us for any longer, especially since it is a very populated country where environmental issues and COVID-19 are worsening the situation.

What is the community’s main wish? To go back to Myanmar or to be allowed to stay in decent condition in Bangladesh?

Go back to Myanmar, of course. That is what we want most of all, but it is very risky and not safe. If that is not possible, we would like for life in the settlements to be improved.

In your opinion, what should the UN and other international agencies do to bring justice to Rohingya people?

Recently the UN International Criminal Court (ICC) considered the Rohingya crisis and it, along with many countries, want to hold the Burmese military accountable. I hope that the UN will indeed hold the military accountable in the ICC.

What is your personal goal?

My personal goal is to help the people of my community and country, and for international communities and agencies to work fast to help them. I want to create a better future for young Rohingya children, in which they have all their rights, including access to education and free movement.

Thank you so much Sahat

Shahida Win

Shahida, can you describe the work you do for Rohingyatographer?

I’m one of the ten photographers in Rohingyatographer Magazine issue 1, summer 2022 and one of two female photographers featured. Nine of my photos are included in the magazine.

I read that, despite working as a doctor’s interpreter, after graduation you followed your passion for journalism. Was there a particular event or issue that stirred the passion? Can you also tell me why you believe journalism is important?

I’m currently working with humanitarian organisations in the camp. With them, I take photographs, which is not my only passion. I also use my voice to advocate for my community such as supporting women and children’s rights, who are deprived of access to formal education. Every morning I go to work at the office of a humanitarian organization, and on the way I take photos of children, women, and men with my phone. I research the stories of the people. I hear them and I motivate them to not be hopeless and express themselves as we are here with them to share their challenges, hopes, and dreams with the world through photography and storytelling. Being a female photographer is very rare in the Rohingya community. I feel very encouraged by friends and colleagues to keep moving forward with my passion to inspire other women in the community. Also I am very motivated to have been given the chance to contribute in the first issue of Rohingyatographer Magazine.

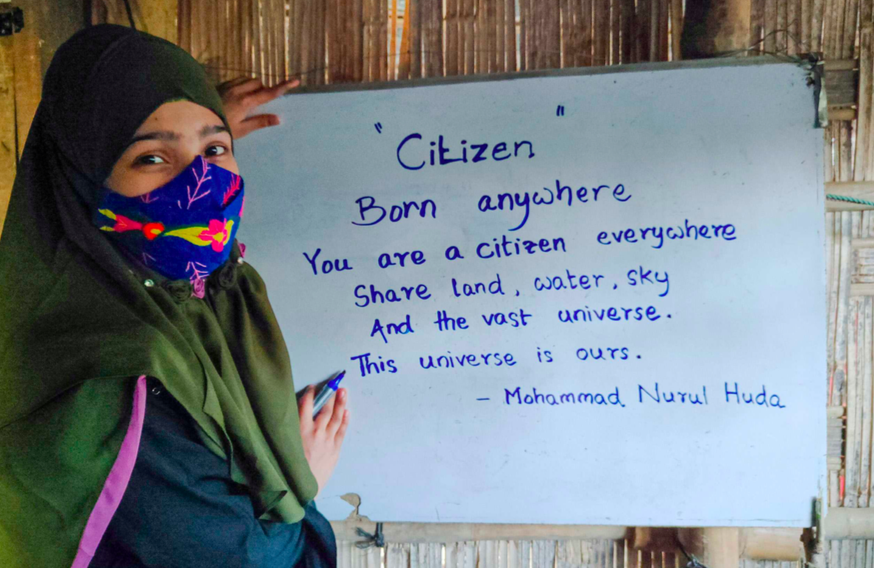

© Photograph by Shahida Win

What are the biggest issues faced by Rohingya women?

More than 60% of Rohingya refugees are children and women. Almost all the Rohingya adult girls in the camp are stuck in this refugee crisis and have no access to school. Because of this lack of education, they don’t get the freedom to express themselves or develop the rights to make decisions for their future.

Can you describe what life is like for a woman living in a refugee camp?

Rohingya women in the refugee camp live a life dependent on others for their every need. They don’t get the right to speak out against the abuse, harassment, and discrimination they are facing everyday. We Rohingya community are at risk of losing a new generation mostly because the women’s world is in darkness. The women’s world must be shined upon by education.

What is your personal goal?

I personally want to be a professional poet and photographer and bring justice and rights to my community. I know I can’t change the whole world by writing poetry and doing photography, but also I can’t keep living voicelessly since I and my community faced genocide. Until justice is served to us, we must keep raising our voices against the injustice and we must keep asking for our rights back, rights that we deserve like other people in the world. So, my aim is to be one of the voices of my vulnerable and oppressed community. I will never give up. Through poetry and photography, I will keep serving advocacy and activism for my community until my last breath. Our voices must be heard.

Thank you so much Shahida

David Palazon

David, can you describe the work you did for Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre?

My background is in design, photography, film, mentoring artists and producing cultural projects, especially on research and visual anthropology. I worked in many places, including Timor-Leste for eight years. Creativity is my everyday bread and butter, it’s all about mapping with communities, production design, creating content and producing outputs with it. During my time in Bangladesh, I was hired to manage the implementation of the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre; it was a complex process that had to be done from scratch. We identified talent like artisans and artists, and in consultation with them we developed a map of their cultural identity. The Rohingya find themselves in some sort of limbo situation, it’s a difficult situation for them to move forward; it’s a stage of constant distress and suffering that affects their daily life, their hope for their future and ultimately their identity and cultural development. Through the project we tried to help safeguard their heritage so it could be used as an educational resource for their present and future. That was the idea behind the centre, which finally opened earlier this year.

What was your role in the creation of Rohingyatographer?

My role is to support their cause and enhance their talent and interests. I do this using my designing, mentoring, and curating skills. I connected with a lot of photographers and artists during my time in Bangladesh, and Sahat was one of them. He reached out to me about publishing his book and I told him I could help him with design; everything went smoothly and we enjoyed working together. Photography was something that was growing organically in the camps, so he suggested involving other photographers and to publish something bigger. He found a team of people and founded the project. We had no money, so it all started totally on a pro-bono basis. In the process, we managed to secure a small fund from the Spanish embassy to support an exhibition in Barcelona but it was complicated because of COVID-19 so it ended up as an online virtual exhibition. The launching of the exhibition was set for World Refugee Day and received quite a lot of media attention. UNHCR got interested and kindly supported a physical exhibition at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka. It’a all about putting things together, that’s what I do.

Your description of the future of the magazine seems to suggest that things are rather up in the air at the moment. Do you see a certain direction the magazine will take in the future? What are your hopes for this project?

In terms of my participation, I am happy to have helped set it up and to help in the future in different ways, with or without funding. For the time being, we all our efforts are on a voluntary basis. We all have other jobs, so this is something we all do on the side. Where the team takes the magazine is up to them, but it has been good to see the participation growing and I have much hope for them. It would be good if we had sponsorship, perhaps a sponsor for each issue. All this needs to be explored. We are already planning the next issue due in December.

As a foreigner, what has your experience with Rohingya artists been like? Did your perspective on the Rohingya crisis changed?

With the Rohingya people my experience was a little different in the fact that, ethnographically speaking, they are not in their natural habitat. So in terms of researching their culture there was a big gap of material culture, so we had to rely much on their memory and oral culture. Anyone in their situation would be in a permanent state of mental distress. Beyond the trauma of having to escape their homeland, they do not have the ability to choose their long-term future. They are really worried about their education and that comes up very often in their photographs. They speak of grief, loss, past memories, and unsettled situations. It is a community that is grieving and has, on the whole, a lot of unresolved personal damage. I believe the practice of photography and art can help them heal a little bit, and convey and express their emotions.

Did your work in Bangladesh change your perception of the Rohingya crisis?

My first hand experience working in the camps gave a clear understanding of the situation they are facing. Sometimes the international media does not portray the reality of the situation, so being inside was for sure an eye opener. They all deserve so much better. They all have had enough of refugee life. They don’t want to be in Bangladesh, they want to go back to Myanmar. In other crises there are corridors for the refugees to establish a new life. But in the case of the Rohingya, they aren’t even recognised as refugees in Bangladesh, they are described as displaced people.

What can the international community do for the Rohingya people and for Myanmar discriminated communities in general?

I suppose people can do very little as individuals, but they can put pressure on those with power to take action, like the Gambia government is doing or the UN could do. The ICJ took recently a step forward so the situation is in the right path. I remember my experience in Timor-Leste, which was invaded by Indonesia for twenty-so years; there was a resistance movement and different pillars supporting their right for self-determination and finally their independence. Many people died and it took long time until their struggle was recognised by the international community. It’s a matter of time.

Thank you so much David

Please consider supporting Rohingyatographer by reading about their mission and consider purchasing this wonderful photography magazine.

© Photographs by Sahat Zia Hero

BACKGROUND

The Rohingya people are an ethnic group from Myanmar, once called Burma. Most lived in Rakhine State on Myanmar’s western coast.

Myanmar is a majority-Buddhist state, but the Rohingya people are primarily Muslim, though a small number are Hindu. The ethnic minority is considered “the most persecuted minority in the world” by the UN.

The story of the persecution has its roots in Britain’s colonization of Burma, and modern-day Myanmar’s refusal to recognize the legitimacy of a community who have existed for thousands of years.

Muslim settlers came to Arakan State, an independent coastal kingdom in what is now Myanmar, starting in the 1430s, and a small Muslim population lived in Arakan State when it was conquered by the Burmese Empire in 1784. Burma in turn was conquered by Britain in 1824, and until 1948 Britain ruled Burma as part of British India. During that time, other Muslims from Bengal entered Burma as migrant workers, tripling the country’s Muslim population over a 40-year period. But although Muslims had lived in Burma for centuries, and although Britain promised the Rohingya an autonomous state in exchange for their help in WWII, it never followed through, and the Burmese people resented what they saw as an incursion of uninvited workers.

Myanmar gained its independence from Britain in 1948. The government didn’t provide for a Muslim state, either. Nor did it acknowledge the Rohingya—a name adopted by a group of the descendants of both Arakan State Muslims and later migrants to Burma. Instead Myanmar worked to cast out the Rohingya people, excluding them from its Constitution and finally driving them out of the country they have been calling home.